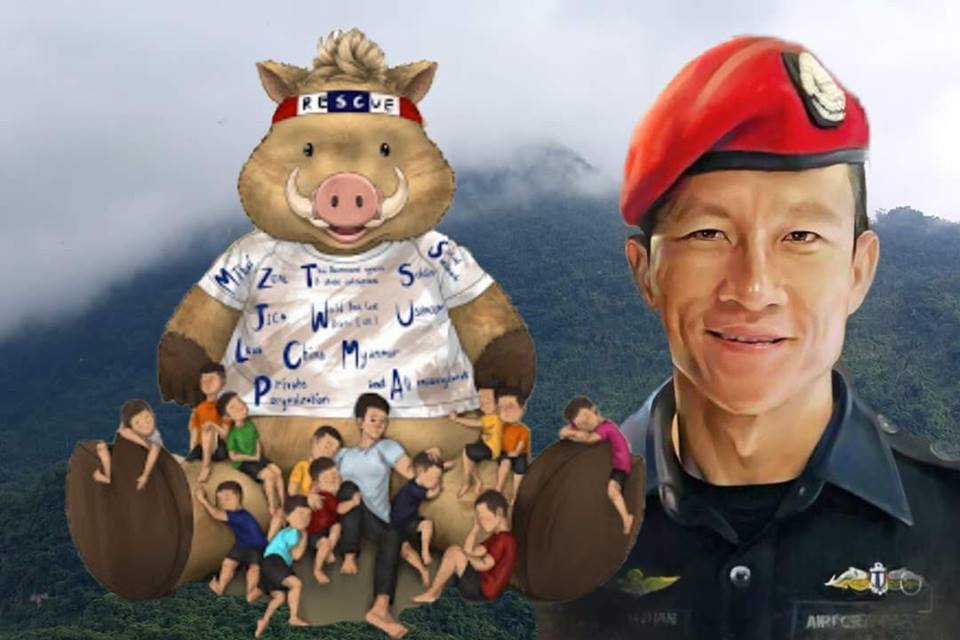

With the Thailand cave rescue operations now completed with the 100 % successful evacuation of all casualties and rescue divers, Darkness Below presents some reflections on this incredible “good news” story. Before reading further, however, let us remember Saman Kunan, the Thai volunteer diver portrayed above, who lost his life while preparing the cave for the evacuation operation. There is nothing more noble than this: that someone will risk their life, and be prepared to lose it, in the course of helping to save the life of someone else.

As cavers, we are all privileged to have some comprehension, however limited, on the nature of caves, the mindset that makes people want to explore them, and the challenges that can present themselves when something goes wrong. When the story first broke that a group of children and their football coach had not emerged from a cave which was now flooded, how many of us would have given much chance of them being found, let alone recovered alive and physically unharmed? Floodwater is totally unforgiving in a cave. Just a few inches of fast-flowing water can sweep you off your feet. Rising water can cut you off from your exit in minutes. At worst, it will take your life.

Cavers better understand the physical challenges of the rescue, although few of us will have accomplished a similar feat. Rescuers were often dragging large amounts of heavy equipment through the cave, not just through dry sections which is difficult enough, but also long distances underwater, fighting the current, and in near zero visibility. This would be a tough challenge for experienced cavers but the Thai Navy divers, especially in the early days of the rescue, overcame hurdles for which most of them would neither have received training nor had any previous experience.

Early in the rescue Vernon Unsworth, a British caver living in Thailand who had explored in Tham Luang cave, began working with the Thai authorities and established contact with British cave divers, and as a result John Volanthen and Rick Stanton quickly flew to Thailand to spearhead the rescue. They were joined a few days later by Chris Jewell, Jason Mallinson and three surface rescuers, and then by three more UK divers. Help was sought from cave divers around the world. The international team brought expertise and equipment and eventually grew to, reportedly, around fifty divers.

As the rescue effort began it fell to the boys’ coach, 25 year-old Ekaphol Chantawong, to keep the group together and safe. There has been speculation about how the boys ended up in the cave, and how the coach came to be with them. We don’t know whether he entered with them or whether he was the first person to attempt to rescue them and became trapped in the process. Either way he kept them together, took them deep into the cave to high ground, and kept them safe and alive until divers reached them. Without him the rescue would have been doomed to failure from the start.

With any human story that gets as much attention as this one has throughout the world, misinformation and speculation often obscure the facts, but on this occasion, despite inevitable confusion at times, the dissemination of news has been excellently managed. The high profile of the British Cave Rescue Council in providing informative press releases may have had a significant part to play in this, certainly as far as the contribution of British expertise was concerned. We at Darkness Below also want to pay tribute to the head of the rescue mission, Narongsak Ossottanakorn, for his regular updates which were timely and informative throughout. It’s also clear that his willingness to accept outside expert help from very early on in the rescue was key to the rescue’s ultimate success, and he, along with Vernon Unsworth, deserve full credit for their efforts.

Regardless of the reliability of the information presented, I am not sure if the wider public fully comprehended the finer details of what was being done to rescue the trapped party. Certainly when at a public-facing event recently, members of my club were asked several times about what had happened, not quite appreciating how the boys had got so far into the cave, and why they could not get out again. But caves and caving are so far from most people’s day to day experiences that perhaps this is understandable, regardless of how good the news coverage might have been.

It was also brought home to me how far the effect of the rescue operation could spread. Once the names of some of the divers were known, it was inevitable that attempts would be made by a news-hungry press to make contact with friends and family members for background information.

Although most cave rescues are much more straightforward, they can become quite complex. The divers in Tham Luang formed just one part of an enormous team, which involved over a thousand people at the cave itself, with yet more involved at a distance. A small army of volunteers spent days searching the jungle for alternative entrances, engineers worked flat out to bring in pumps to divert water from the cave, and in the cave itself, drillers brought in rigs attempting to drain it from below. Many more people were involved supporting the rescuers, locals prepared food, local ladies even volunteered to clean the hastily installed toilet facilities. More than one commentator at the site reported their surprise at how well ordered and well maintained the area around the cave was.

The small world of the UK caving circuit became apparent to me as the operation progressed. I was surprised to learn that one of my caving friends was instrumental in introducing one of the UK divers to caving when he was a youngster. Having kept in touch with the family, he was aware of the press attention they were receiving and spent a day helping to keeping them at arm’s length, while there was a great deal of uncertainty over how the operation would pan out. Everyone has the potential to help in some capacity, however peripheral.

What effect might the rescue have had on the public’s perception of caving and of cave rescue? Will it be fully appreciated that the success of the operation was in no small way due to the dedication and professionalism of voluntary experts? Also, is it widely understood that Cave Rescue in Britain is a concept based entirely on unpaid cavers helping their fellow cavers when they get into trouble? It’s even more unlikely that most non-caving members of the public will appreciate the full enormity of the achievement of Rick Stanton and John Volanthen in fighting their way underwater, against the current and successfully laying line leading to the discovery of the boys and their coach. We know that Rick and John will feel that saving the team was tribute enough, but they are owed much more. Nevertheless, John’s interview on his return to the UK admirably demonstrated his wish that everybody in the team should take credit for the successful recovery of all thirteen casualties.

I expect that caving will continue to be viewed as an activity undertaken by either brave or foolish people, who have less regard for their own safety than is to be expected of “normal” people. I have lived with this attitude from friends and acquaintances for as long as I have been exploring the subterranean world, and have no reason to think that this will change. What Tham Luang has proved is that at times the World needs people like these, and that when enough of them from different backgrounds and countries come together we haven’t yet found the limit of what can be achieved.

The magnitude of the rescue operation was, by any measure, huge. The bravery and skill of so many people is recognised, and not least the courage of the trapped party, who have been through a great ordeal. The emotional effect of the time spent underground, completely unaware of efforts to locate them is something that only those who experienced it can comprehend. The frustration of having to remain in the cave for several more days after they had been found, and to wait for your turn to be taken back to safety will have required tremendous patience. And to be evacuated by diving through the water and the challenging cave environment will have needed complete trust in those leading the party one by one to safety. All I can say is that when I was at a similar age, I simply cannot imagine that I would have had the strength of character and mind to stay calm under such pressure.

Shortly after the rescue came to an end it was reported that the father of Australian cave diver and consultant anaesthetist Richard Harris had died. We at Darkness Below extend our sympathies to Richard and his family.

Peter Burgess

Cave Rescue in Great Britain

British cave rescue teams are run by volunteers and are totally reliant on donations to fund their ongoing work. There are fifteen teams in total. If you would like to help by donating to your local rescue team you can find them via the British Cave Rescue Council website here.

If you are an active caver, give some thought to joining a rescue team local to you. Please don’t feel that you have little to contribute: any team will welcome genuine interest and be happy to take you on board in a useful capacity. Please bear in mind that although cave rescue teams away from the main caving regions may not see regular operational activity, the experience you have by joining them may prove to be very useful. From my own experience, I was involved in a SMWCRT incident last year and the comms training I had with SECRO allowed me to get involved which freed up others to do casualty recovery.