Alan Jeffreys dips into his bookshelf again to take a look at another caving classic.

Back in the day when I was just starting out on a speleological career, seeking books from public libraries almost inevitably involved reading French authors. Although there was a smattering of British volumes, most of them dated from the turn of the 20th century and seemed to me rather antique in their approach. Conversely, a steady stream of works from distinguished French explorers, translated by R.G.L. Irving or E.J. Mason, provided accounts of spectacular deep caving far beyond possibilities provided in the UK. Naturally Norbert Casteret featured prominently, but descriptions of world record explorations to caves such as the Trou de Glaz, Pierre St Martin and the Gouffre Berger fired my imagination (and envy). Tales of daring-do down potholes over 1-2,000 feet deep seemed to be arriving ten a penny.

Taking a slightly different approach with this book Lavaur, an engineer who rose to become co-founder and Vice President of the French Speleological Society and Hon. President of the Speleo Club of Paris, began his caving career tentatively in 1929, investigating caves in the Dordogne region. He met Martel, and recounts a highly amusing tale of his first descent with Robert De Joly down the Aven de Cassan near Séverac-le-Château in southern France from which he emerged bruised by falling rock and unable to continue under De Joly’s unsympathetic leadership. He then describes the progress of French speleology following World War Two, including the siege of La Henne Morte, before providing a detailed account of explorations he led into the far reaches of Gouffre de Padirac, thereafter turning to his other passion, cave diving.

It may seem vaguely amusing now to read of these primitive expeditions, mostly into vertical Vauclusian springs, using equipment of breath-taking (pun intended), almost clockwork simplicity, wearing cumbersome rubber clothing (neoprene, the ‘sponge-rubber’ material mentioned in the text, not then universally available) and base-fed lines, but it vividly highlights how the subsequent evolution of techniques witnessed, some 60 years later, the triumphant through trip from Padirac to St George’s Spring, a result Lavaur could only dream about following some hair-raising exploits in the latter.

The author follows a similar pattern to Casteret (at least in the English language versions) in filling the latter half of his book with discussions on techniques, equipment and uses of exploration, again all very interesting in hindsight in understanding how far developments have evolved since the early 1950’s. Indeed this is one important reason for reading the book – not only to show how advanced we have become, but to emphasise just how much these relatively early explorers were able to achieve. Accustomed as we are to sliding up and down string with ease, it is so easy to dismiss the struggles and sheer determination of people clad in primitive clothing humping extremely heavy tackle great distances underground, even on occasion camping far from entrances. This book is not just a quaint window into the past, it is a tribute to great pioneers and deserves to be read as such by the current generation.

Reviewed by Alan L. Jeffreys

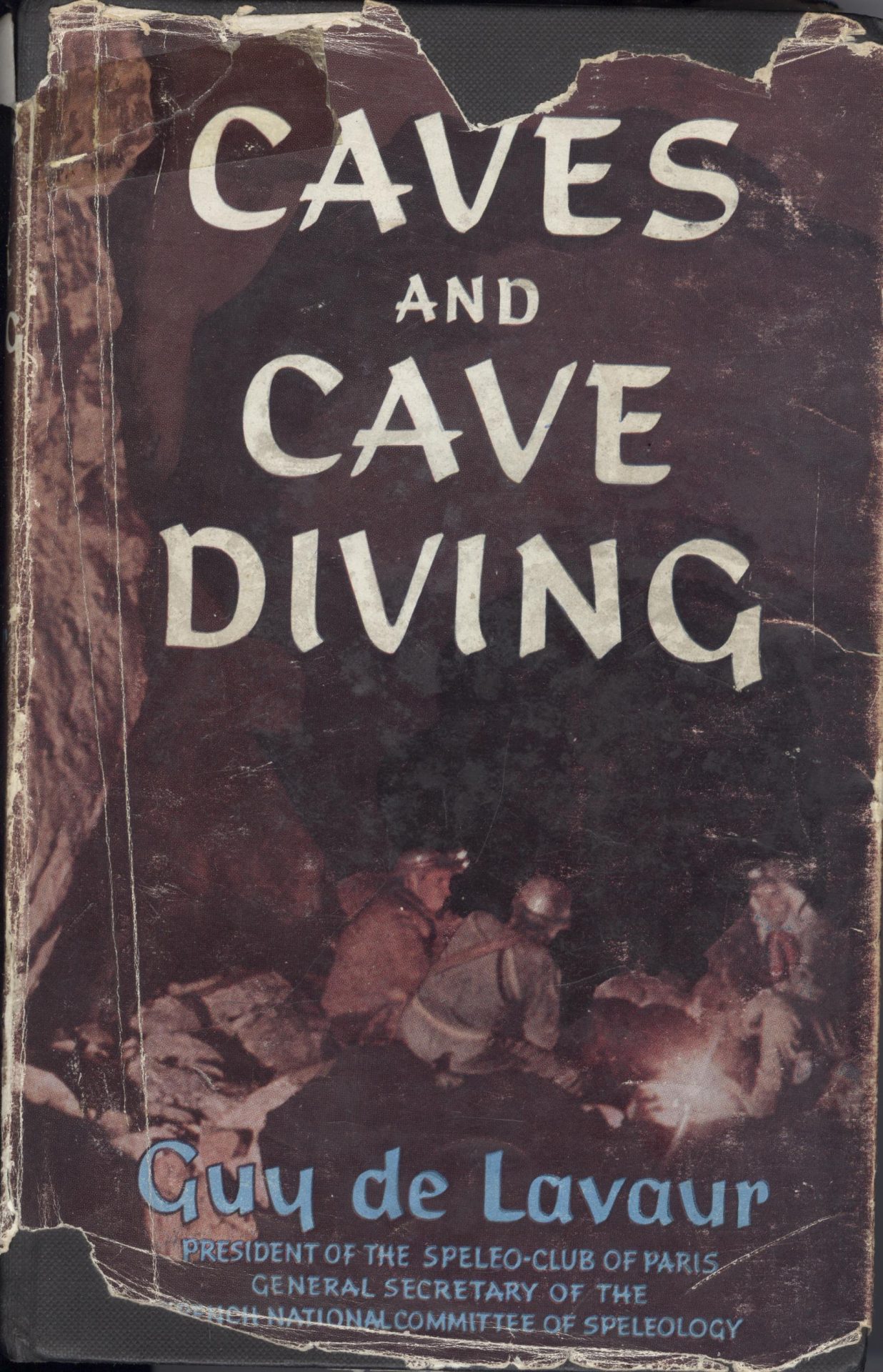

Caves and Cave Diving

Guy de Lavaur

Robert Hale Ltd

Published 1956

175 pp

12 photos

20 drawings.