The BCRA’s 30th annual science symposium took place at Keyworth,hosted by the British Geological Survey. I attended the Saturday session and was impressed by the depth and variety of scientific work being undertaken by British cavers.

The morning session kicked off with a description of palaeokarst features found in the Pielkhlieng Pouk-Krem Sakwa system in Meghalaya, India. Mark Tringham described finding pinnacle epikarst with up to 15m of relief surrounded by sandstone and coal infills which have been exposed within the cave. The talk was illustrated with some really beautiful photographs from Mark Burkey and Chris Howes, amongst others. These was also a quite remarkable stream passage in the upstream part of the system seemingly formed entirely in sandstone, though that was not the focus of Mark’s talk. The second talk also featured Meghalaya, where Dan Harries has been finding blind cave fish larger than any previously described elsewhere. Are they a new species or merely a variety of the surface species known as the Golden Mahseer (Tor putitora)? Only the DNA will tell. The final talk of this session was something completely different. Dominika Wroblewska described and showed the art that she has been producing as she follows and learns about the caving community and about caves.Some of Dominica’s works illustrate this article.

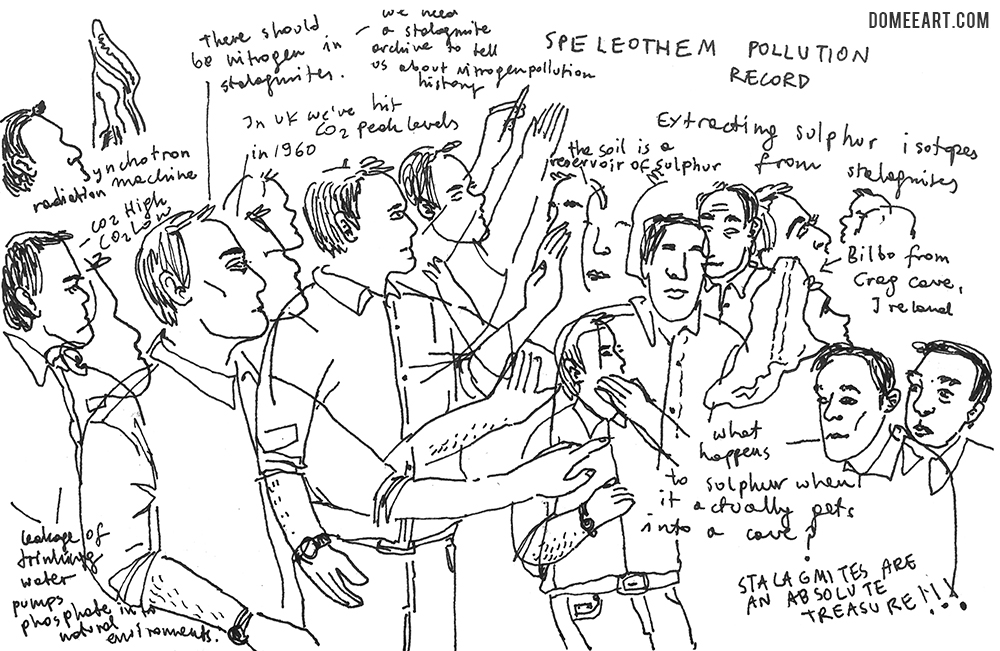

The morning was rounded off by the keynote talk Exploring the speleothem pollution record given by Peter Wynn. Peter described work by himself and many collaborators, teasing out very high resolution archives of sulphur, nitrogen and phosphorus emissions recorded in stalagmites. This is ongoing research, but it is clear that the techniques developed by Peter and his many collaborators will be extremely useful in tracking these pollutants over time and from region to region. It is now known, for instance, that the UK hit ‘peak sulphur’ in the late 20th Century and levels are now in decline thanks to regulatory legislation. This was a fascinating and important talk.

The BCRA AGM was held before lunch. This was mainly a matter of reports, but it was interesting to hear that BCRA Council is actively considering changing its current close relationship with BCA and would like to hear from its members with their views on this.

The post-lunch session kicked off with two presentations about springs: Chas Yonge described the Banff Hot Springs in Canada from a karst perspective, pointing out that the main elements in involved in turning snow falling at an elevation of over 2,000m into hot groundwater (67°C) are extensive thrust faulting, karst dissolution process at depths of over 3km and suitable amounts of time. Then John Gunn described the complex nature of the flows in the Peak Cavern system in Derbyshire and how the flow from Main Rising and Whirlpool Rising switch and oscillate. John stated that this was probably the most complex flow regime in the world, but they now have a lot of high (1- and 2-minute resolution) data and are coming much closer to understanding how it works. The final talk in this session saw Phil Murphy giving a tour of the low-lying karst areas on the south eastern side of Morecambe Bay. None of the caves here are, as yet, of any great size but it is clearly an area that warrants further attention, both speleological and archaeological.

Catrin Fear began the final session with an account of the re-assessment of the archaeological finds from Frank I’Th’Rocks Cave in Derbyshire. This cave was excavated in 1925 by Leo Palmer but since the publication of his report in 1926, most of the finds have remained unstudied in Buxton Museum. Catrin’s work has shown that the cave was utilised from the Upper Palaeolithic through to the Georgian period, but that the majority of the evidence, including the human remains, relate to the mid-late Romano-British period. This work, as with other recent work in collections elsewhere, highlights the importance of re-examining archival collections using modern techniques.

John Gunn then returned to give a progress report on work at the cave science research centre at Poole’s Cavern, Buxton. A lot of monitoring equipment is now in place and good data sets are now being collected for the most commonly collected cave climate parameters, including air temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, rainfall and CO2 concentrations. Over the past year several student science projects have taken place within the centre. Much of this work would simply not be possible if this facility, in a managed show cave, was not available. Matt Rowberry, then described one project actually taking place at Poole’s. He and his colleagues are currently working to use magnetic sensors to monitor movement across a bedrock fracture. Interestingly, data from the sensors is analysed in real time at the Institute of Physics at the Czech Academy of Sciences and the team are using AI techniques to devise early warning systems for potentially hazardous environments.

The final presentation, by Tim Atkinson, gave a geomorphic background to the field trip to Creswell Crags the following day. It is interesting to note that work in the 1980s there was amongst the earliest uses of Uranium series dating for such purposes. I was unable to attend the field trip, which was led by Andrew Chamberlain and included opportunities to view the Palaeolithic art in Church Hole.

Thanks are due to BCRA, especially to Gina Moseley, the lecture secretary, for organising such an excellent symposium, to the BGS and Andy Farrant for hosting the event and to Donna Farrant and her children for manning the sign-in desk and baking some wonderful cakes, with proceeds of sales to BCRA!

Correspondant: Graham Mullan. Original artwork is © Dominika Wroblewska <domeeart@gmail.com>