Alan Jeffreys recently came across a curious manuscript entitled Concrete Evidence, a speleo novel by Victor Stephen Wignore and reviews it here for Darkness Below.

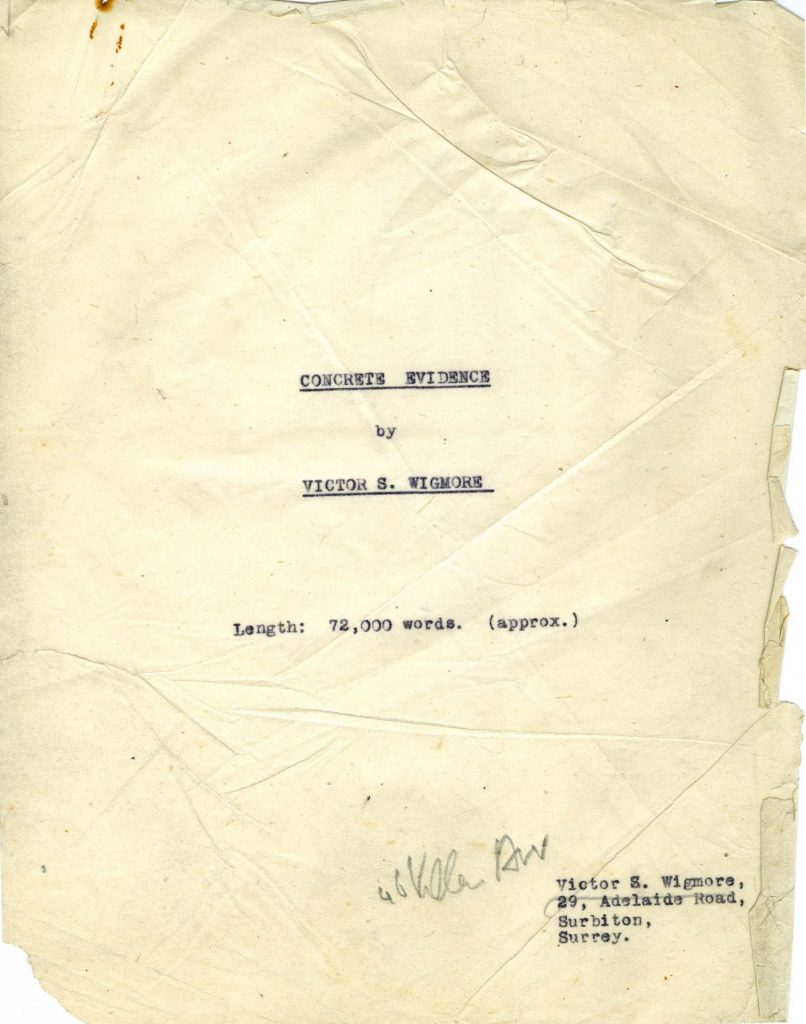

Squirrelled away amongst the papers of Eli Simpson and the now defunct British Speleological Association is a typed, carbon copy manuscript on quarto paper of a ‘thriller’ amounting to some 72,000 words involving cavers, drug smuggling villains and concrete. This latter features considerably, not surprising as Wigmore, a sometime member of the BSA Council, was a concrete consultant throughout his professional life. One of his achievements was assisting in the construction of ‘Mulberry’ floating harbours for the D-Day invasion in 1944. In 1947 he served as president of the Society of Engineers and was a member of the Geologists Association from 1931.

Born in 1898, Wigmore was active before the 2nd World War, having commenced caving on Mendip with Gerard Platten, joining the Wessex Cave Club in 1935, and was associated with Platten’s ‘Dragon Group’ during their explorations in Dan yr Ogof. A chamber beyond lake 4 – Wigmore Hall – is named after him. He remained in the BSA into the 1970s and was a Council member until 1964. The manuscript is undated, but it probably dates to before the 2nd World War.

The book is divided into 23 chapters and opens with the discovery of artificial interference inside a cave system, linked to the disappearance of a local man, thought to be lying under boulders within the cave passage. As investigations commence, the cavers, led by the redoubtable Roger Stanson, suspect dirty deeds to be going on at a local concrete works and with the help of an inside mole, his eventual girlfriend Irene Wilson, the caving team undertake to track down and reveal whatever crime(s) the owner of the factory might be involved with.

That is the plot in brief, and it rolls along at a pleasant pace, although it would appear that none of the cavers ever seem to work as they are always available to participate in various nefarious capers to obtain evidence to back up their suspicions. They are all mobile with motorbikes and cars and display the chin-up British pluck which is a feature of pre-war fiction. There is a love interest thread too, as a romance slowly (ever so slowly and in a very British fashion) develops between Roger and Irene.

The story would appear to be set in a fictionalised Mendip area (here called ‘Wyndip’), although some of the place names, such as ‘Craglands’, a mansion purchased by the central villain, sound more Yorkshire in flavour (vide ‘Cragdale’ the pre-war BSA headquarters). All caving tackle is of course quite old fashioned, with common use of candles and rope ladders, and descriptions of caving activities show a cavalier disregard for the difficulties in clearing boulder chokes (both natural and engineered) using only muscle power and the odd hauling rope. Lesser criminal gang members are sketched as rather corny muffler-bound ‘Cor blimey’ characters, so not very believable judged against today’s standards. In fact the whole plot line is rather thin by those same standards. Needless to say the whole affair is solved for the police rather than by them, but then the heroes are cavers so what’s new?!

The entire manuscript reads more like a teen novel than adult fiction, with the possible exception of the ‘love interest’, but even that is rather harmless compared to what youngsters can now easily obtain online. Whether the book is worth publishing is moot. No doubt fanatical book lovers would wish a copy for completeness, but I don’t think there is a commercial case to be made. However, Wigmore was a published author of at least two books on concrete (!) and one children’s fiction book about caving, again set in the Mendip region (‘Adventures Underground’, 1935), so he didn’t do too badly.

Reviewed by Alan L. Jeffreys, with thanks to Harry Long, Martin Mills and John Crae for background information on Victor Wigmore.