The 2018 annual conference of the National Association of Mining History Organisations was hosted jointly by Gloucester Speleological Society, Royal Forest of Dean Caving Club, Hades Caving Club, South Gloucestershire Mines Research Group and Clearwell Caves, and held at Park End in the Forest of Dean. There was a comprehensive list of field trips available over the weekend, and a full lecture programme. All the presentations took place in the Garden Room of the Dean Field Studies Centre. There were two full days of lectures, with Mining in the Forest of Dean as a common theme.

Dr. Mark Tringham, a retired professor, geologist and caver, was our first speaker on Saturday. His easily understood but nonetheless thorough analysis of the structure and geology of the Forest provided an excellent framework for the rest of the lecture programme. The lecture provided an overview of the origins of the geological structure – the folds, fault lines, and unconformities, and a comparison with the nearby Bristol and Somerset coalfields.

The second speaker was Dan Howell, the current Deputy Gaveller for the Forest of Dean. He is a graduate of Camborne School of Mines, and well-grounded in the Forest’s laws. Dan spoke about his role, and started by explaining the provisions of the 1838 regulation of the Forest of Dean freeminers. He is responsible for issuing the right to work a “gale” to anyone that fulfils the requirements to be a Forest of Dean freeminer, namely to have been born within the bounds of the Hundred of St. Briavels, and to have worked in a mine for 366 days. Over 4000 gales have been granted from 1838 to 2018. Dan’s responsibilities also include maintaining and keeping records of mines and investigating old mining features such as shafts etc. Freeminers can extract both coal and iron within the Forest of Dean.

Ian Pope, well-known owner of publisher Lightmoor Press, described the range of Forest of Dean collieries and the nature of the coalfield. Ian presented the stories of a succession of coal mines, who worked them, how they were operated, and illustrated the talk with a nice set of photographs, of both the shallow easily worked mines operated by small freeminer concerns, and the deep pits that worked the seams only accessible to larger enterprises with the capital to set up pumps and large-scale extraction.

Steve Grudgings and David Hardwick presented some of their research into the use of early mine engines in the Forest. This focussed on the adoption of the Newcomen atmospheric engine by Forest of Dean mines, which they conclude was done quite late in the story of the development of steam mine pumping engines. The first such engines to appear in the Forest did so around 1777, at the time when they were being replaced elsewhere by the newer and vastly more efficient Boulton and Watt engines. The use of old Newcomen engines from elsewhere, such as Cornwall, was possibly due to those mines seeking to dispose of their old unwanted pumping engines after 1760. There is very little to see today, with the ruins of two engine-houses that are likely to have housed early steam engines.

Roger Deeks presented a very well researched biography of Arthur Clifford (1881-1961), and his role in Mines Rescue in the Forest. Clifford’s father was involved in the adoption of the Siebe-Gorman “Proto” rebreather apparatus for rescues in the North Staffordshire coalfield, and Arthur followed in his footsteps, taking advantage of the equipment to extinguish oil-derrick fires in Mexico, before returning to Britain in 1915 to enlist after the outbreak of war. Arthur’s expertise was put to good use, training rescue teams at the front in the techniques of mine-rescue, which was desperately needed in the ongoing and immensely dangerous tunnelling operations under enemy lines. He was recalled to the UK in 1917 and awarded the Meritorious Service Medal for his efforts at the front. In 1918 he was recalled again from France and given the job of managing the recovery of 155 bodies from the Podmore Hall Colliery, usually called the Minnie Pit disaster, a harrowing task which took 18 months to complete.

Arthur Clifford moved to the Forest of Dean and became superintendent of Mines Rescue in the coalfield. He wrote “The Rescueman’s Manual” in 1922, and ran the Forest Mine Rescue School until 1959.

Before the programme moved on to the next speaker, Roger Deeks introduced us to one of the miners trained by Clifford at his rescue training school, Royston Pritchard, now in his 80s. Royston gave an account of the two mine rescue incidents in Forest mines which he attended in his time as a team member.

Paul Taylor then presented a very apt lecture to follow Roger’s, talking about the development of the Gloucestershire Cave Rescue Group since 1962, including their current cooperative role in mine rescue within the Forest. This development has provided a very useful capability, using the skills of local cavers and freeminers, and has facilitated the continuation of freemining, since a local competent mines rescue team is on call should the need ever arise. The great increase in accessible caves in the Forest since the team was formed was illustrated, along with the huge advances in available equipment and technology.

The Gloucestershire Cave Rescue Group

David Sables, former Yorkshire miner, related the story of two underground locos from Rossington Colliery, Yorkshire, which closed in the 1990s. The locos have subsequently been rescued and are displayed at Clearwell Caves.

Ian Wright followed, and described the widespread “butty” system of employing miners, and the problems it caused for some people in working mines efficiently. Colliers were employed as independently contracted miners, who employed a team to work a pitch, and were paid per ton. Until the 1930s, the butty system effectively controlled the labour process.

Bob Wolensky of Wisconsin, Professor of Sociology and assigned to University of Exeter, presented a comparison of the butty system and its equivalents, used in the Pennsylvania anthracite belt of North America and in Britain.

The social event on Saturday evening was a “faddle”, held inside Clearwell Caves, and gave everyone a chance to catch up with those who had opted to attend field trips during the day.

Sunday’s programme of lectures continued with the theme of Forest of Dean mining, and commenced with Ian Standing, one of the Forest of Dean’s four verderers. Ian described the Forest iron mines, and the market for the ore extracted. Early mines were worked for ore that was used in iron production using the bloomery process, wherein iron is separated from the oxide ore below the metal’s melting point, the resulting bloom requiring a forging process to “hammer” out the molten slag from the hot mixture, producing wrought iron as an end product. This process fell out of use by the 1550s. By the late seventeenth century, the easily-won ore had been exhausted. The charcoal blast furnace had been developed many years earlier in the Weald, but was adopted very late in the Forest of Dean. This technology produced molten iron which was cast into pigs. Earlier discarded iron cinders were often used as a useful source of iron for this, as well as mined ores.

Forest of Dean iron is low in phosphorus, an element which made iron from other places such as the Weald more brittle. Nevertheless, competition from Swedish iron extraction was too great, and by the early 1800s, the English charcoal blast furnace trade had been severely curtailed.

Ian described the few extant iron furnace remains in the Forest of Dean.

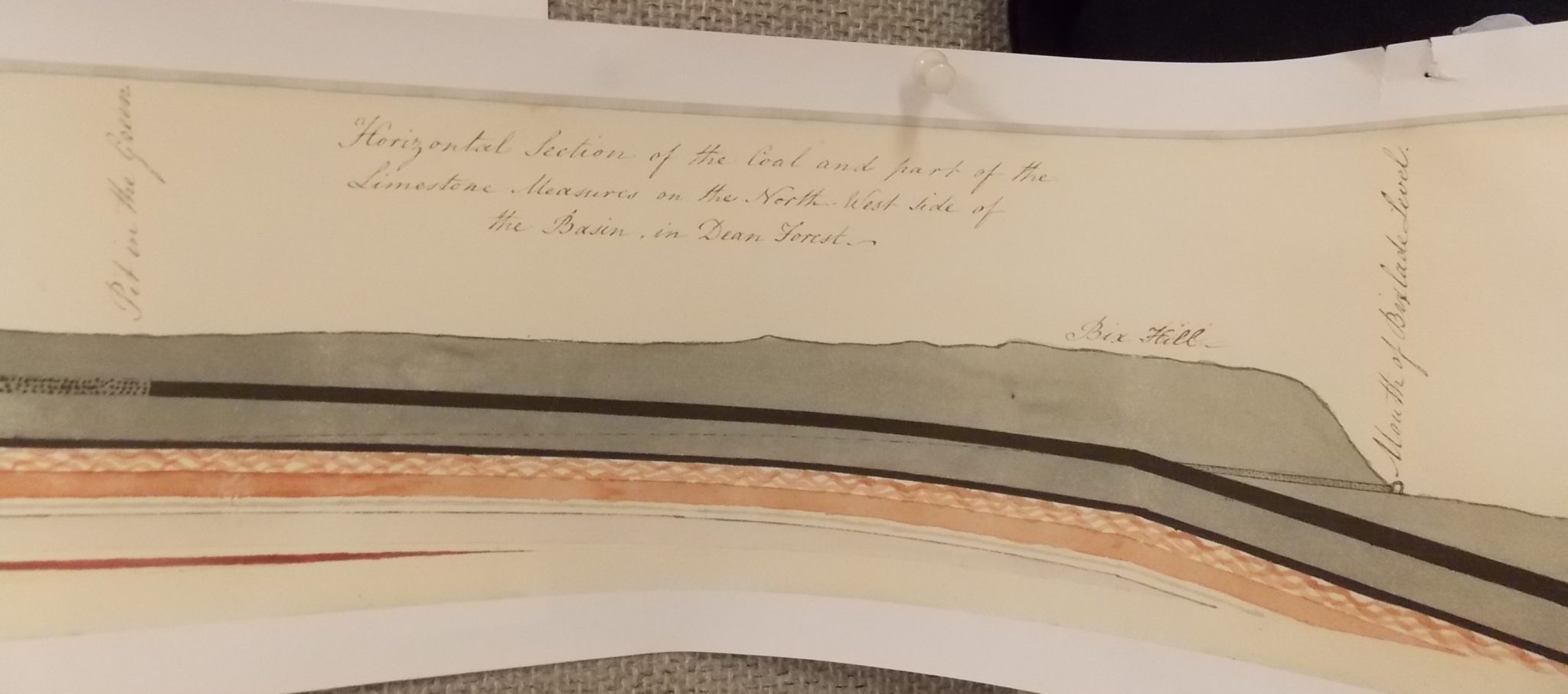

Dr. Cherry Lewis, retired geologist and honorary research fellow of the University of Bristol, related the story of David Mushet, father of the arguably more famous Robert Mushet who investigated and developed processes for manufacturing good quality durable steels. The talk focussed specifically on David Mushet’s geological research in the Forest of Dean, which resulted in a detailed section being produced, showing the positions and depths of the coal seams in the coalfield. Having described the story of the section, and its publication, Cherry Lewis postulated that because many dozens of copies were made of the section, it is likely to have been part of a prospectus promoting the Bixlade Colliery which features on the section. Mushet’s work was considered a very accurate and valuable contribution to our understanding of the Forest’s geology well into the twentieth century.

John Barnatt has recently retired from the Peak District National Park. He has undertaken research into the fire-setting method of mining, and has recently conducted research into firesetting to extract iron in the Forest of Dean where archaeological investigations have taken place at Great Doward, in what are known as the “Pancake Mines”. Radiocarbon dating of material recovered is underway, and the results are expected to demonstrate that the activity was medieval or post-medieval in date.

George Price is an active Gloucestershire caver who has taken a great interest in bats, and is a member of the Gloucestershire Bat Group. George gave a good summary of the state of the bat population of the Forest of Dean, and explained the monitoring that is done each winter, and how different factors can affect populations, including the protection of summer maternity roosts.

David Hardwick presented the conference with an analysis of early horse-drawn railways, and how they developed in the Forest of Dean. He demonstrated what evidence to look for and showed us a number of photographs of lines that survived in use into the photographic era. He described how although the lines were built by private railway companies, the wagons were hauled by independent contractors, not unlike the present national situation with Network Rail, and the various private train operating companies.

Dr. Peter Claughton, a regular speaker at NAMHO events, spoke about the Ebbw Vale iron and steelworks, and the sources of ore that it used. The proximity of the Forest of Dean, might have made it a useful source of iron ore, however Peter explained why this was not the case. Domestic sources of Ebbw Vale ore were described, mainly low phosphorus ores from West Somerset, but also significant supplies from Northern Spain, and Southern Spain, and more recently Algeria in the twentieth century. Forest of Dean and Glamorganshire ores were very low in manganese which made them less suitable for the Ebbw Vale company.

A short presentation followed, additional to the published programme. Dr. Simon Timberlake of Cambridge University, presented the results of radiocarbon analysys of an antler pick, found in the Carnon Valley streamworks in Cornwall, in 1790. The pick was uncovered 40 feet down in the placer tin deposits being worked extensively near Devoran. The results confirmed that the pick was from the early Bronze Age, approximately 1600 BC. Simon added some speculative ideas on early Forest of Dean mining, particularly with reference to hammer stones from a scowle near Lydney.

Ian Pope spoke about where the Forest of Dean coal output was sent. Early transport from the area was focussed on using the rivers Wye and Severn as the two principal transport routes before road and rail improvements. The Thames and Severn Canal provided a route for coal to be sent east towards London. All land transport in the early years would have been by packhorse, and although turnpike roads improved access, the roads were tolled and were not necessarily kept in good order. Early tramroads, as described earlier by Dave Hardwicke, were developed which greatly improved the transport of coal to docks on the banks of the Severn, and again when standard gauge railways arrived. Records from this time demonstrate that there were three types of customers for coal shipments. Collieries had their own wagons to take coal to the docks, or further afield, coal factors (large merchants) were bulk buyers of coal from the mines who also provided their own wagons, and smaller coal merchants also bought coal. Wagons for the three types of coal buyer were evident at the colliery sidings and docks. Most coal was exported via Lydney Docks in small ships, and sent to Bristol, south-west to Devon and Cornwall, and a significant amount to Ireland. Export via Lydney Docks ceased in 1960. The Severn Bridge had been built to improve sales of coal by rail across the Severn via Sharpness.

Appropriately, our last speaker was Rich Daniels, who is one of the Forest of Dean’s current freeminers. Rich spoke about the current mining activities in the Forest, and his optimism for the future. Rich helps out at the part showmine part production colliery at Hopewell. He is chairman of the Forest of Dean Freeminers’ Association, and is one of the four Dean Verderers. Until a few years ago, the future of mining was very uncertain. The main issues facing the freeminers were the possibility of a Mining Inspectorate Fee for Intervention, which was likely to put all the freeminers out of business, all mining activity being done at a subsistence level. This has been dropped after discussion with the Mining Inspectorate. The lack of deputies was also going to be a major issue, until mining legislation was relaxed to accommodate this. The third issue was the cost involved in having mines professionally surveyed, but thanks to the appointment of the current Deputy Gaveller, this is also no longer a problem, as this can now done easily using modern surveying techniques thanks to the office of the Deputy Gaveller, maintaining records being one of his responsibilities.

A further important issue is that of difficulties attracting younger people into freemining. A Heritage Lottery scheme, “Foresters’ Forest”, has been established, and includes mining in its remit. It encourages youngsters to take up an apprenticeship at a freemine. The provision of Mines Rescue has been resolved through the joint venture with the Gloucestershire Cave Rescue Group. There are currently six working pits, and most are worked part-time. There are currently thirty registered freeminers.

As one of the requirements of becoming a freeminer is to be born within the Hundred of St. Briavels, the lack of any maternity units in the area is a significant worry. Currently, mothers resident in the Forest of Dean are taken to Gloucester to give birth, but there is a campaign to restore maternity services to the area, and the future is by no means all bleak.

The weekend was rounded off with a ride on the Dean Forest Railway, from the terminus at Park End, down to Lydney Junction and back, hauled by the Great Western Railway Prairie tank 5541, which, unfortunately, failed on the return leg, unable to raise sufficient steam from the poor quality steam coal it was carrying. Nevertheless, the evening was sunny and warm, and it was certainly a better place to be stranded on a train than the outskirts of Croydon on a wet, cold winter’s evening. Rescued by the 08 class shunter “Gladys”, we arrived back in Park End intact, albeit a little late.

The 2019 Conference will be held in Mid-Wales and is to be hosted by the Cambrian Mines Trust. The theme is “Mine exploration as a research tool – applications in mining history, geology and archaeology”.