A full mining history conference complete with field trips, steam trains and beer was recently held in North Yorkshire, from 17th to 20th June. Peter Burgess attended and gives the event an enthusiastic thumbs up!

Retirement brings mixed blessings for those who are fortunate enough to have sufficient income to live reasonably well. On the plus side, travelling long distances can be done at leisure without the constraints of work schedules. On the down side, the costs can be significant, especially with the fast-rising costs of fuel we are experiencing this year. North Yorkshire was an area new to me and quite a way to travel, but I was keen to visit and discover something of the rich mining history I had heard about.

The event was hosted by the Cleveland Mining Heritage Society and was centred on Grosmont, a small community a few miles inland from Whitby, where the lectures, and other events were scheduled to take place, and is conveniently located for many of the field trips that had been laid on. Grosmont has a rich mining and industrial past.

The accommodation venue was at a tiny community called Esk Valley, either in the Holme House bunkroom, or camping in the adjacent field. This proved to be a delightful spot, away from main roads and within earshot of the North Yorkshire Moors Railway heritage line. We were regularly treated to the highly nostalgic sound of distant steam train whistles, bringing back early childhood memories of night mail and goods trains echoing around the town where I grew up. Campers could use the non-sleeping facilities in the bunkhouse which were more than adequate. Holme House is a pleasant 10 to 15 minutes’ walk away from the lecture venue. There is even the site of a 19th century ironstone mine adjacent, with conserved surface remains to view.

Two days of lectures were served up on Saturday and Sunday, with the theme of “Industrial Minerals”, with an emphasis on the Cleveland area. The area is well-known for the production of iron and steel and for the current Boulby potash mine, but perhaps less known are workings for whinstone, jet, salt, and alum. The various lectures covered all this and more. George Featherston hosted both days of lectures, and introduced each presenter, and managing the programme in a delightfully informal and humorous manner. The lectures were held in the 19th century St. Matthews’ Church in Grosmont.

Simon Chapman started Saturday morning describing the development of ironstone mining in the Eskdaleside area, close to Grosmont. This included small-scale shallow workings in the immediate area of St. Matthew’s Church, where the lectures were taking place. One early level runs only a few metres below the railway line, an unnerving experience for anyone underground when a train passes overhead! Workings were developed as a result of the opening of the Whitby and Pickering Railway, which provided a convenient means to get the iron ore to market. An interesting relic of the early mines was a length of cast iron plateway found in situ, with “Whitby Stone Co” cast on the underside, confirming who was working the ore in the early 19th century. Other later workings extended down the Esk valley from Grosmont, mainly bord and pillar workings, but with some attempts to use the long-wall working method. The last mine to close was Eskdaleside Mine in 1915.

Neil Rowley, known to many mine explorers as the now retired person who facilitated visits to Boulby potash mine until 2015, looked back at the first 50 years of the mine, how the deposits were first discovered, and how the mine workings were opened up and developed. The potash deposits worked there occur in deep concealed Permian strata below the Lias, Keuper and Bunter beds. The talk explained geological challenges which added to costs and, sadly, accidents. These have been largely overcome and the mine is now more profitable and considerably safer. The market is now changing from the potash mineral first worked, being a mixture of potassium and sodium chlorides, to polyhalite, a complex sulphate of potassium, calcium and magnesium. One significant challenge has been demonstrating to a conservative agricultural community that polyhalite fertilisers are as effective as the former type that was produced. The talk concluded with a short piece by Peter Woods, one of the two geologists after which the Woodsmith Mine was named, the workings being opened up as a new polyhalite mine in the area.

Saturday morning concluded with a talk on Whinstone Mining in the North York Moors, presented by Rick Stewart. Rick is more usually associated with the mines of Devon and the Tamar Valley, but is also familiar with the working of basaltic andesite from the Cleveland Dyke. The rock was mainly extracted for use as a roadstone, but was also worked for setts for street surfaces at one time. The dyke is between 20 and 30 metres in width, and is the cause of some striking landforms where it runs through the area. The stone was worked using a combination of narrow opencast pits, and mined levels, and was last worked underground in 1964, at Bradley’s quarry. Rick led us on a tour through the numerous workings starting from the north west, working south eastwards. Leeds Corporation worked Cliff Rigg quarry for a while, producing stone setts to use in the city streets.

After a break, the afternoon commenced with Mark Hatton presenting The life, leaving and legacy of German miners in Elizabethan Keswick. Mark posed the question, did the 16th and 17th century German mining in Cumbria influence the way the later Industrial Revolution developed across Britain? Miners from German-speaking provinces in Europe were invited to explore and exploit metalliferous ores in England commencing in 1564, setting up the Company of Mines Royal. There was no German nation at the time, and it is more likely they came from regions such as what we now call Austria, but this is speculative. Mark showed us the evidence of the mines and the area used for smelting, and described the social impact of this sudden influx of strangers. Surviving evidence includes traces of leats, the mine workings, piles of ore and spoil heaps. The spot where smelting operations took place is still metres deep in smelting waste. Mark believes the answer to his question is yes, in the way that they demonstrated successfully how to organise and control the technology in a systematic way, without which large-scale development of any industry simply cannot take place.

Geoff Taylor gave a historical talk on the Rosedale Railway. This remarkable line was constructed specifically to serve the ironstone mines of Rosedale. With the mines at an elevation of 1200ft, this required the construction of a long incline to bring the ore waggons down to Battersby Junction and on to the steelworks of Middlesborough. With the line serving such a remote and desolate place, disruption during severe winters was a regular issue, and a special set of snowploughs were kept permanently on the summit level, fitted with a refuge cabin behind the plough equipped with survival rations where the gang could stay safe in the event of becoming stranded. The closure of the mines in 1925 resulted in the closure of the line by 1929, after the extraction of calcine dust from the spoil heaps ceased. Conservation work and the promotion of awareness of the area is part of the Land of Iron project, which Geoff explained. More information on the Land of Iron project.

The final talk of the Saturday sessions was on a surprising topic, the development of the trade in fossil reptiles from the Whitby area around the world. Roger Osborne, the geology curator of Whitby Museum, first outlined the local geology, and in particular the alum shales, as this is where significant reptile fossil discoveries have been made. A market in these fossils gradually developed from the early 19th century, particularly in the years when having a collection of curios was the fashionable thing to do. As museums developed later in the century, the marketplace grew. Roger illustrated the price inflation for large fossils over the years, as demand mushroomed. He described disputes over ownership, in particular the case of an alum quarry where the operator’s lease allowed them to exploit the alum only, and selling a large fossil they found was deemed to be outside the terms of the agreement and the specimen had to be returned. More information on the Geology and Fossil collection at Whitby Museum

Day two commenced with Dr Karl Houseley, who reviewed the different kinds of iron ore, and the economics that come into play when finding the sources of iron. Karl listed and described the main iron minerals that are found in iron ores of various kinds. Historically, low grade sedimentary ores were widely used in Britain. These came from a variety of geological contexts, but would nowadays be considered highly uneconomical. The iron content was usually a long way below 50 percent. Nowadays, banded ironstone formations are worked. These are worked extensively in Australia and comprise iron ore banded with jasper and quartz. Where weathering has separated and removed the quartz, this yields the best ore. 62 percent is usually considered the lowest economic iron content for a workable ore. Other factors that are relevant for a quality ore are the presence of other elements, detrimental or beneficial, and how easy it is to process the ore to a pelletised form where the lumps or pellets are sufficiently consolidated to maintain their integrity in the smelting process. Karl described the various processes used to crush and separate the iron content, removing those minerals that might cause problems during smelting. Karl stated that 10 percent of the world’s energy consumption is used in breaking ores. That surprised me.

Dr Peter Claughton spoke on the Supply of fluxes and lining materials for the British steel industry, with a focus on the problems experienced during the First World War. Peter described the use of limestone, fluorspar, and refractories such as ganister in the production of steel. Changes were forced on the steel industry in the First World War when low phosphorus iron ores became far less available and Britain had to rely on British ores with significant phosphorus content. This required the industry to switch to using the basic steel process which overcame the problems caused by the phosphorus content. Although limestone is widely available throughout Britain, a shortage of labour meant that there were supply challenges. This was overcome by using PoW labour. Fluorspar was required as a flux in the production of special steels using the electric arc furnace. Basic linings for furnaces increased the use of dolomite. The vital supply of materials for the steel industry caused the recall of men from active service, and the use of female labour. Listen to Peter Claughton talking about iron and steel resources in the First World War.

Dr Rob Vernon’s lecture was on The Search and Exploitation of Phosphates in the Nineteenth Century. The traditional source of phosphates was bones. As demand increased, extreme actions were taken, including the use of mummies from Egypt and digging up the bones of fallen soldiers in European battlefields. The explorer Alexander von Humbolt, in the early 1800s, promoted the use of guano from Peruvian islands, where huge deposits of seabird excrement had built up. The dry climate meant that there had been no significant erosion of these, and a trade soon started, exporting the guano on an industrial scale. This started in 1838 when the first cargo load of guano was offloaded in Britain. It was known that treating sources of phosphates with sulphuric acid created a soluble superphosphate, which became the primary phosphate fertiliser. British mineral sources of phosphates included the Bala limestone of North Wales, which contains apatite. Extraction of this commenced in the 1870s. Mining of apatite ores in Spain commenced in the 1860s, from the Extremadura and Murcia regions. Another source of mineral phosphate in Britain was coprolite deposits in the Lower Greensand of Cambridgeshire. Many shallow pits were sunk in the 1880s to extract this.

The afternoon started with a lively presentation on neolithic salt production in North Yorkshire. Dr Steve Sherlock described recent archaeological excavation work near Boulby, where convincing evidence of neolithic salt production has been uncovered. Previously it was thought that salt production, by the evaporation of sea water, had not started until the Bronze and Iron ages, evidence for which is plentiful. Steve suggested that the site excavated, being a short way inland, has survived whereas other neolithic salterns may have been located at beach level and have consequently been lost to coastal erosion and sea level changes. Although the salt working site discovered has all the hallmarks of an Iron age site, radiocarbon dating and other dating evidence place this site firmly in the neolithic period. See the neolithic salt excavation in this Channel 4 news story.

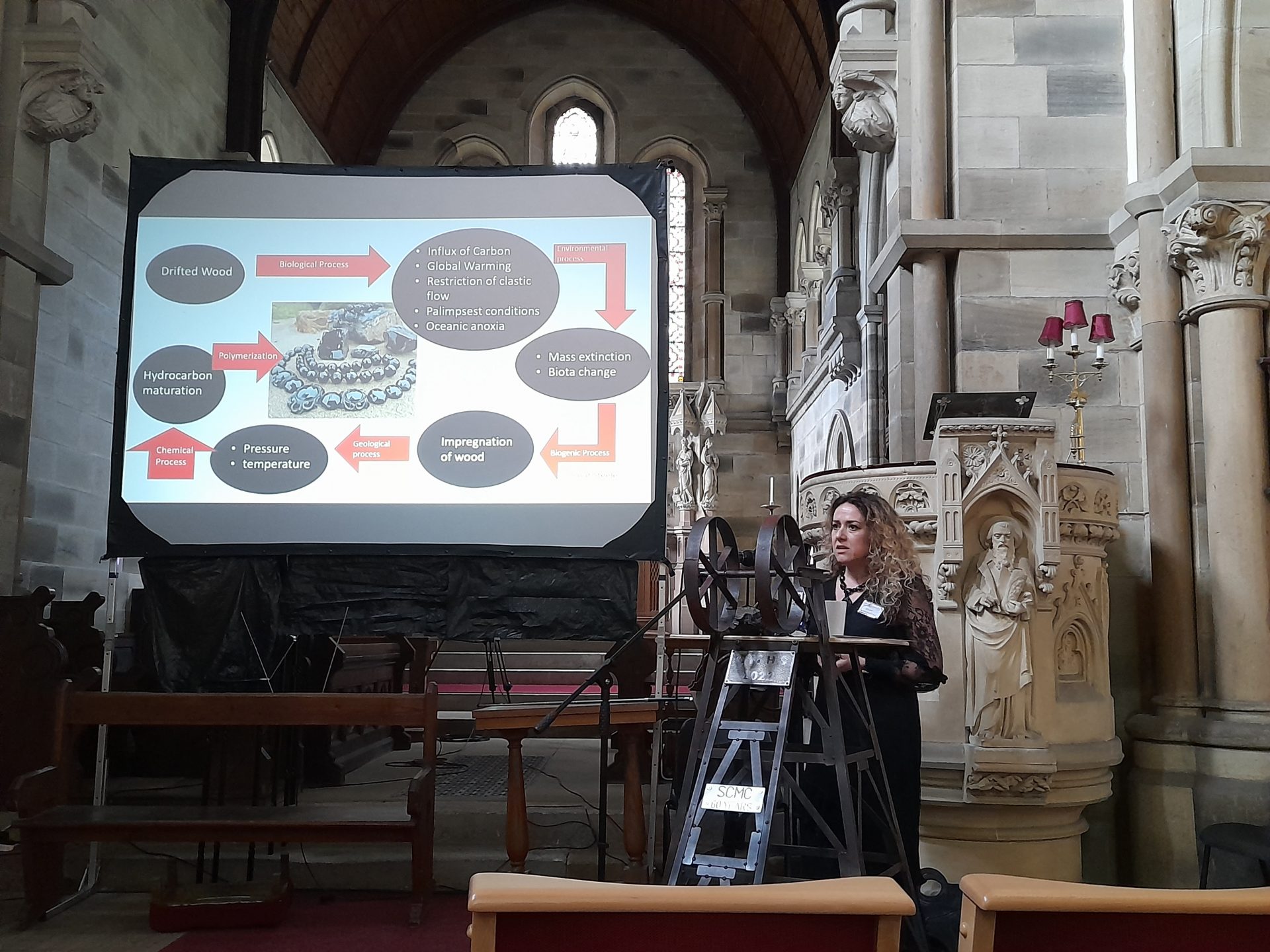

Sarah Steel believes greater clarity is required in the identification of jet and jet-like materials, in both commercial and historical contexts. Sarah is a geologist and commercial jet worker from Whitby and is keen to replace a culture where few people are bothered about what it is or where it comes from, with a better appreciation of provenance and the variety of substances marketed as jet. Sarah explained the long history of jet processing, possibly starting as early as the neolithic period, and continuing through Roman times to the present day. Sarah suggested that “gem quality hydrocarbons” better describes the various forms of jet that exist, and that she is keen to find a technique that can differentiate between jet products that originate from different locations around the world. The use of materials other than Whitby jet, from abroad, threatens to undermine the important trade in genuine jet from the Cleveland region. Learn more about jet research at Sarah’s website.

The last talk of the conference was by Roger Pickles who described the rise of the alum trade on the Yorkshire coast, how it developed into a heavy industry, and it’s decline. He described how the alum shales were burnt in huge clamps for many months, and the alum then extracted from the burnt shale. He explained the purification process in alum houses along the coast, and the production of a by product, magnesium sulphate, otherwise known as Epsom salts. More information about the alum industry.

On Friday and Monday, and throughout the weekend, field trips were laid on, both into old mines and on the surface. Mineworkings for ironstone and jet were on the agenda, as well as walks to see local industrial history, alum works, and the railway and ironstone workings at Rosedale. Visits to the motive power department of the North Yorkshire Moors Railway at Grosmont were also arranged, and there was also plenty of scope for delegates to explore by themselves.

Included in the visit to the railway depot was a tour of an unusual workshop, where “Armstrong Oilers” are made. These are sprung loaded pads of carpet material which use cotton wicks to transfer lubricating oil from an oil box to the axle boxes of locomotives and rolling stock. Tammy Naylor was our guide here, and her role is to load, set up and operate the loom that produces the fabric element of the oilers. Her husband fabricates the steel springs and frames for each oiler. They have collected a large number of templates and specifications for hundreds of different oilers, each one specifically designed for a particular item of rolling stock. They are the only fabricators of these vital parts for heritage railways and other operators of vintage vehicles, such as the trams that still run in Hong Kong.

On Friday afternoon, the field trips included a tour of Grosmont to see local geology and industrial archaeology. Tammy Naylor led this walk, which included a good view of the beds that underlie the village in the sides of the river gorge of the Murk Esk river, followed by a tour of the streets where we were shown the locations of former abattoirs, ironstone mines, and blast furnaces. What remains of the original horse-drawn Whitby and Pickering Railway before its conversion to the current steam railway was pointed out. A walk around the site of the blast furnaces led us to the former location of a plant that operated in the 1940s. long after the closure of the ironworks to convert the slag into slagwool, used for building insulation. It was clear that if you want to know anything about the history of Grosmont, Tammy is the person to ask first!

Monday’s excursions included a walk at the Rosedale ironstone mines, and a visit to the coast at Sandsend to see evidence of alum working and jet workings in the cliffs. The latter was led by Simon Chapman and Steve Livera. The day started cool and overcast, but by lunchtime we were enjoying unbroken sunshine. The route took us along the course of the former Whitby, Redcar and Middlesbrough Union Railway, past former alum quarries and the remains of calcining heaps and steeping tanks. The latter were very obvious at the Deepgrove alum quarries, and as we approached the now sealed Sandsend tunnel, we were led down a steep path to the base of the cliffs at Deepgrove Wyke. Here, now the tide was receding, we could safely walk the foreshore to see where adits had been driven into the cliffs in search of jet, and could examine geology freshly exposed where a section of the cliff had fallen only some months previously. The rocks here bear evidence of the Toarcian oceanic anoxic event, a time of mass extinction during the Jurassic era, when ocean temperatures are estimated to have risen by 6 degrees Celsius as the result of major volcanic activity and the release of a large amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

With this sobering reminder of what may be in store for our planet in the not too distant future, we returned to Sandsend in glorious weather, and enjoyed a well earned tea at the beach café, bringing the 2022 NAMHO Conference to a satisfactory end.

I cannot finish this account without acknowledging the supreme efforts of the organisers which resulted in another very enjoyable and successful NAMHO event. Chris Twigg deserves a special mention for his excellent communications and organisational work in the lead up to the weekend, and the sterling efforts of Tammy Naylor, who continually seemed to be in several places at the same time, leading walks, touring the oiler workshop, fetching things to and from the lecture venue, sorting out issues at Holme House, and so on. Thank you to all who served teas, looked after the audio-visuals, organised beer, fetched extra beer from the nearby social club when the supply ran out, arranged the fish and chip supper, booked the Sunday evening meal at the Station Tavern, and the list goes on.

Next year’s NAMHO Conference will take place in Grasmere, Lake District, over the weekend of 7th – 10th July.