Peter Glanvill has dug out some of his older photos to show the nature of cavers’ attire from the 1950s to the end of the 1970s. Although not an old photograph, we see here what cavers may have worn when the sport was in its infancy. Basically, you would be concerned to keep warm, and to wear clothes that would never again be suitable for anything other than caving. Old jackets, sweaters and thick trousers, and more often than not, no helmet, just a thick cap to provide a little protection from banging one’s head. It was probably a very good incentive to move around with a great deal of care.

Photos and captions by Peter Glanvill. Commentary by Peter Burgess.

As caving progresses into a clear well-illuminated future, with super-bright lamps, caving suits that seem to last forever, and cavers complaining of feeling too hot in their fleece-lined garments, let’s remind ourselves of how things were, and how, despite the limitations, great things were achieved in exploration and discovery.

There was a time when there was nothing you could buy that was remotely designed for use by cavers. The closest you might get would be to find a miner’s lamp or helmet to use, but the great majority made do with a builder’s helmet tied on with a single chinstrap, a carbide lamp (which were originally made as miners lamps), or a hand-torch. Perhaps the first most important change in cavers’ attire came with the wetsuit. This provided some warmth, and protection from the sharp rock, until these home-made garments started to fall apart at the seams. But they did allow cavers to explore very wet caves in a degree of comfort.

If you went caving, unless the cave was dry and dusty, you accepted that at some point you would get wet, cold, and probably very muddy. What you were wearing would feel heavy, uncomfortable, grit would work its way down to your skin, and anybody who put those same clothes back on the next day was considered either very brave, or very keen, if not a bit mad.

Despite all the limitations of cavers’ kit, some remarkable achievements were made. I am not even going to begin to describe the hemp ladders and ropes that were in regular use before caving shops started to offer electron ladders and synthetic ropes of various sorts, not least because that was well before my time.

I’ll wager these youngsters’ mothers were not particularly overjoyed with handling the weekly laundry. There are some interesting helmets here. I can spot at least two miners’ helmets made from compressed card, impregnated with a resin to make them stiff and to provide a modicum of protection. One problem with these helmets occurred when they started to absorb water, when they would quite easily become soft and rather too flexible. Cavers would often give them a generous coat of paint to stop this happening. Here we see that a delicate shade of pastel blue has been used. I wonder whose dad had some spare tins in his shed after some DIY decoration?

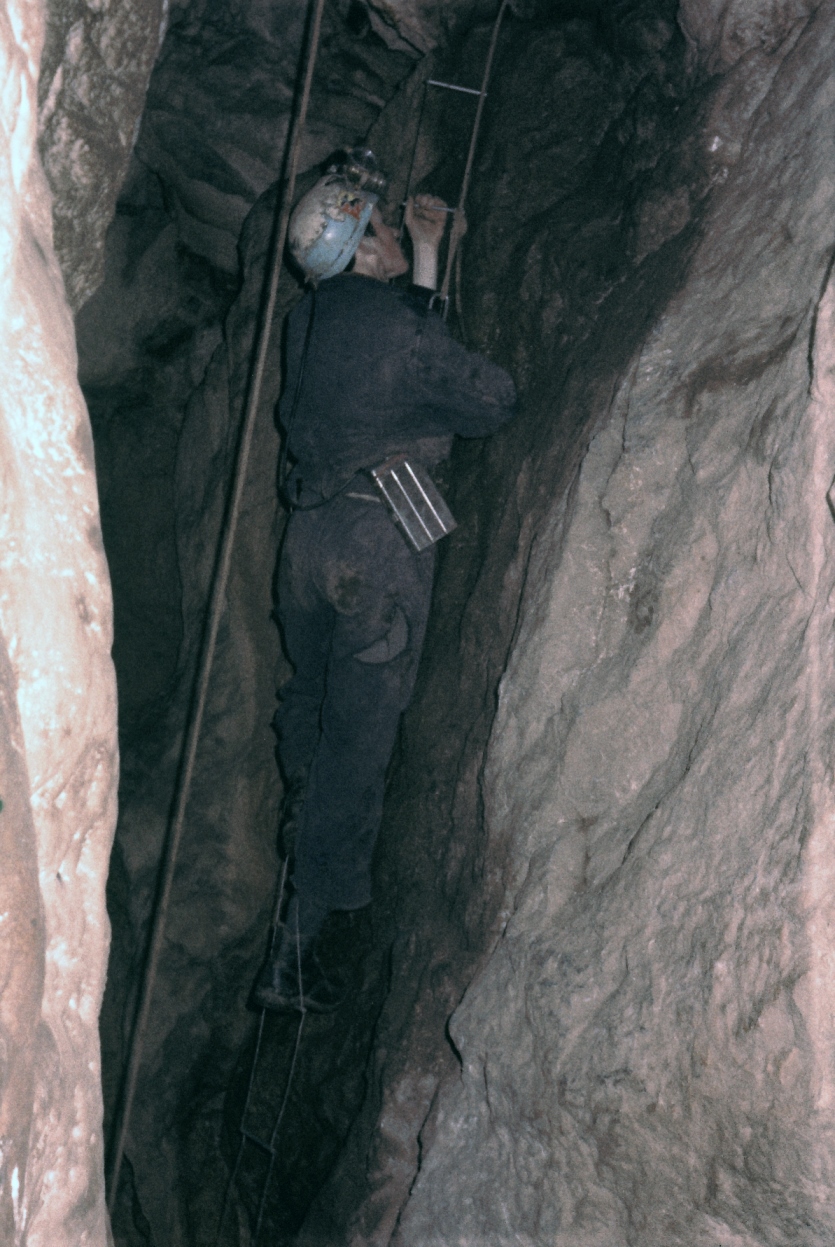

By the 1980s, wetsuits were the norm. Divers, of course, found them absolutely essential, using very thick neoprene and hoods. Martyn is wearing what was effectively a builder’s safety helmet – although probably marketed by a caving supplier as a caving helmet. Did he ever master the knack of rolling an electron ladder neatly? In order to fix two waterproof torches to a helmet, it would have been necessary to drill some holes in it. Martyn’s main lamp appears to be the superb Oldham miners’ cap lamp. Whether the battery fixed to his belt was the original lead-acid set, or an adapted one containing ex-military NiCad cells is a good question. One problem with the lead-acid cells was that water could easily enter them via vent holes, and it was equally possible for strong sulphuric acid to leak out through the same holes, wreaking havoc with clothing, ropes, slings, and skin. There was even a caving sling marketed that would change colour if attacked by corrosive electrolyte, so you knew immediately when you had ruined it.

This photo illustrates very well the Premier carbide lamp. These brass lamps used calcium carbide and water to generate acetylene gas, which burned with a lovely bright yellow flame, and had a very distinctive smell. A charge of carbide might give you four hours of light, before you had to put more in. The more conscientious caver put his spent carbide in a bag or other container and took it away. Others simply tipped the contents into a corner of the cave, and you still come across little piles of it in some caves today, as it doesn’t go anywhere by itself. Understandably, carbide is almost entirely a thing of the past. Peter has not only got hold of a better helmet, he is now sporting a nice electric lamp. It isn’t an Oldham though. And he seems not to trust it too much, as he is still hanging on to his old faithful Premier lamp.

Another one of those card helmets is being used here. I know a caver who continued using one of these well into the 1980s. This view shows clearly another kind of cell that cavers used. This was the Edison NiFe lamp. The battery you can see has three cells containing potassium hydroxide solution, providing 3.6 volts for his caplamp. Like the Oldham with its lead-acid cells, these too were prone to leaks, with unpleasant consequences if you didn’t notice early enough. Caving shops offered a choice of belts and slings, those that were resistant to acid, and those resistant to alkali. You were supposed to use the correct one, and if you had paid attention in your school chemistry lessons, you could make the correct decision when ordering your kit.

Ted is wearing the ubiquitous builders-type helmet, but note also the accessories. The rope is a hairy hawser-laid rope, which, one would hope is synthetic and not hemp. Natural fibre ropes were the only option before polymers were developed, and had to be very carefully inspected, cleaned, and dried out to minimise the chance of them rotting. The ex-military ammunition box was about the only thing available for carrying stuff into caves, like first aid, photographic equipment, or lunch. The sound of metallic boxes clanking in narrow passages was quite usual. Army surplus stores were visited by cavers about as often as caving shops.

The Texolex helmet was popular for some years in the 1970s, here being worn by Derrick and Liz. This was another miners’ helmet, but was made from a much stronger resin-bonded material. I loved my old Texolex helmet, until I discovered that it didn’t take kindly to too much side force when being packed into a kit bag. However, they were light and comfortable.

Everybody here is probably using a wetsuit as their normal caving attire. Dave on the right has probably got one under his oversuit. I don’t recall orange suits being available back in the late 1970s, so this may be a protective industrial one. Abseiling on a caver’s rack or a climber’s “Figure of Eight” was common, and there are three of the latter visible here. The lack of ascending kit shows us that this was probably a through trip, and possibly done using improvised harnesses made from a tape sling. The yellow protective tape seen on the seams of Graham’s wetsuit would regularly peel off and have to be stuck back using special adhesive. Mending wetsuits became a regular job for cavers. Helmets were still a mix of Texolex, hard plastic builders’ style, and card ones. I am sure Graham had been wearing a helmet – but I’m not sure the dark glasses were too helpful underground.

Here we see another NiFe cell, full of caustic potash. Abseiling on a doubled rope was sometimes done, if the rope was then later used as the lifeline for a ladder ascent. The state of the ladder wires is interesting – it looks like it has suffered from some forceful and rather hasty rolling technique!

If Michael wasn’t wearing a wetsuit under those grots, he would have been feeling mightily cold very quickly.

Having spent many hours myself wading through very deep water in flooded mine tunnels, I know that the minimum you needed under your grots was wetsuit leggings and wetsocks. You would have to be very careful to keep your carbide lamp lit in wet caves.

Clean fertilizer bags were a must to protect mum’s car seats after caving. And it would be next to impossible to use the boot for nice shopping after it had been on a few caving trips. I hope Nick invested some time cleaning the car, in the days before “car valeting” had been invented.

If you have ever body-lifelined anyone, did you ever have to arrest a fall? You were relying entirely on holding the rope tightly to your body to provide the friction to do it. Wearing gloves was probably a good idea as well, particularly with a hard, abrasive hawser-laid rope, such as we see here. Good belaying devices were simply not around in the early days. It also helped if you attached your belt to a fixed belay so you were not pulled over the edge.

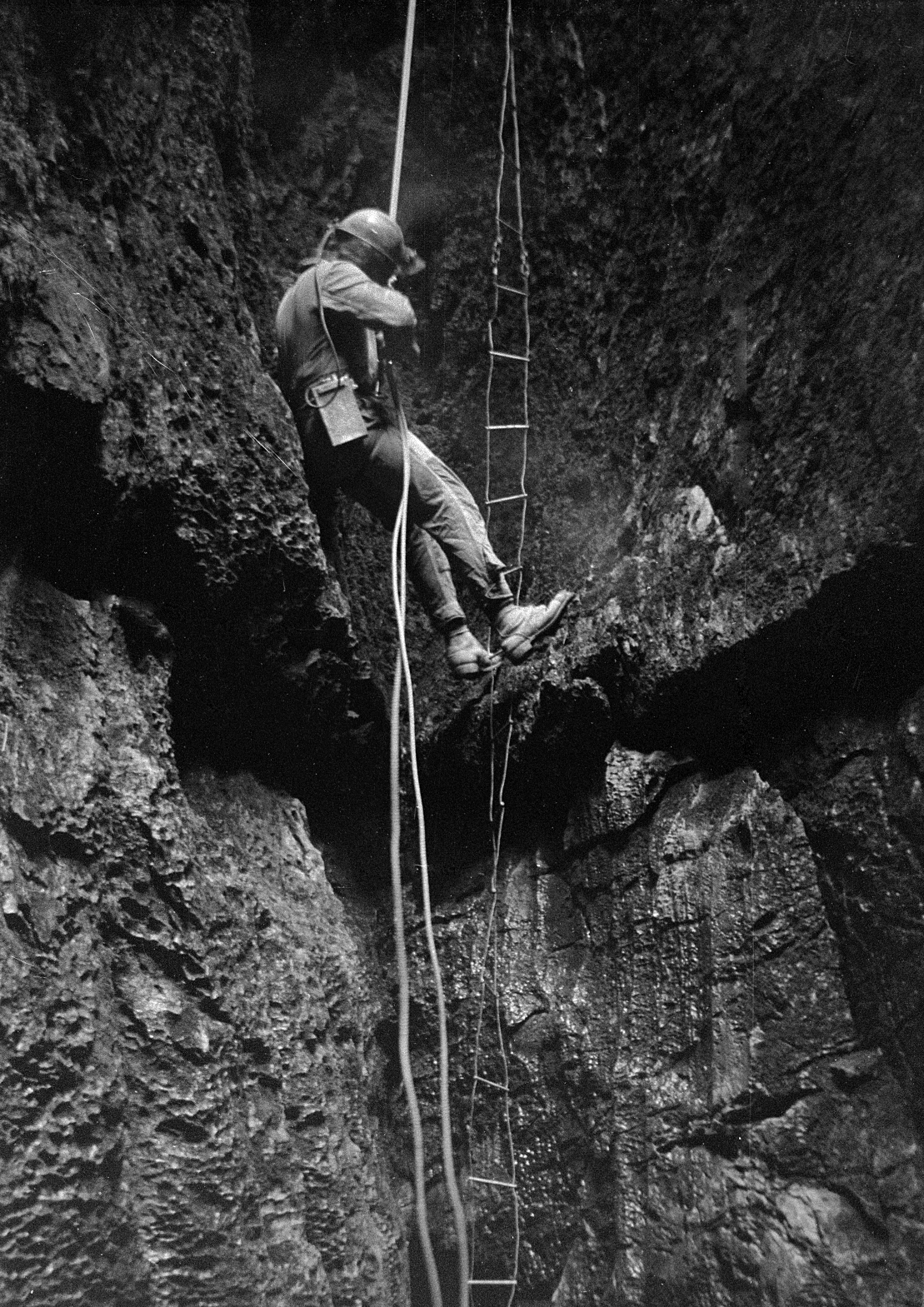

Laddering deep pots was slow and hard work. But before single rope techniques, there was no alternative. Guide books listed all the pitches with ladder and lifeline length requirements as standard. This photo shows the “grots over wetsuit” attire which provided a little more protection from heat loss, and also stopped sharp rocks ripping bits out of your precious wetsuit which you were probably getting fed up repairing.

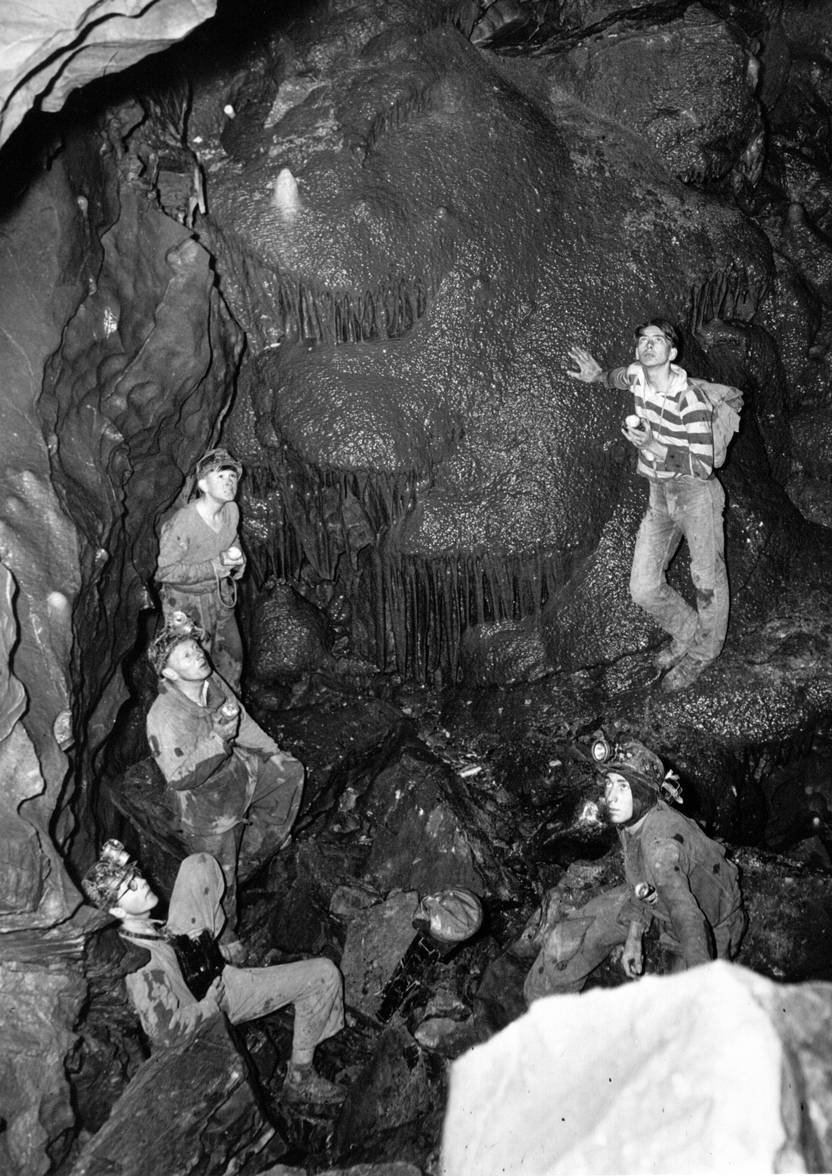

Finally, a lovely image from the 1950s. We see an assortment of lamps ranging from carbide lamps, to cycle lamps and hand torches. One caver has yet to get himself a helmet, and is probably a rugger player, and thinks his shirt can’t possibly get any muddier than it does on the pitch. It is from cavers of this time that our many clubs were formed in the 1960s and 1970s.