Naughty boys, grand follies, an underground control centre for a railway and a Quaker congregation falling through the floor into the cellar … Peter Burgess gets to explore Dorking below the surface in a book that went underground in his own house for a while!

It is with some embarrassment that I am finally writing this book review. The author, Sam Dawson, kindly sent me a copy of his book in the latter months of 2019, and my first instinct was to compose a review of it over the Christmas break, knowing I would have plenty of time to read it all. When packing my bags hours before leaving for a few days of festivities, I scoured the room for the book, but to no avail. Now, at the end of June, it has finally resurfaced – literally – as it had been lurking buried at the bottom of an under-bed drawer, and I just cannot imagine how it got there.

However, now I can apologise to Sam for apparently ignoring his work for well over six months, and let you all know what a great book it is. There are 11 chapters covering the various aspects of underground sites in Dorking, with further sections introducing the reader to underground Dorking, emphasising the historical importance of surviving subterranea, a list of sites to visit and two pages of useful references.

To give you a good insight into the book, I won’t dwell on its style, presentation, and readability – all of these get top marks. What follows is a chapter by chapter summary of the book, so you can judge for yourself how comprehensively Sam covers the subject at hand. After all, one of the primary reasons underground nerds like us buy books is to read facts and stories about underground places.

Tales of mystery and imagination

Pride of place as the subject of the first chapter in the book are the South Street, or “Butter Hill” Caves, open for public tours through the work of the Dorking museum. Here we learn about the intricate three-dimensional nature of the complex, about how the caves proved useful for storing various forms of alcoholic beverage, some interesting ideas about why someone went to all the trouble of digging a subterranean staircase to the bottom of a well, and that there is a naughty boys’ entrance. Every cave should have one of those.

The gardens of Eden

We move on to places where the combination of excessive wealth and easily diggable ground gives rise to subterranean features of grand folly, or at least of little practical purpose. The closest stately grounds to the centre of Dorking is at Deepdene, where the soft sandstone has been tunnelled into and reformed by former owners fortunate enough to have occupied the property. Follies, grottoes and pointless tunnels are all described and explained. The grounds of Deepdene (the house has long since gone) also contain a complex of tunnels specifically dug to house an emergency control centre for the Southern Railway Company during the Second World War. Subterranea at Betchworth Castle to the east are also covered here, as are the grottoes of John Evelyn’s 17th century mansion at Wotton House to the west of the town.

Digging for victory

The so-called Box Hill Fort is described here; in reality it was a mobilisation centre constructed in the 19th century as part of a fairly short-lived plan to build a defensive line south of London. Sam describes his personal experiences of exploring the site as a boy, when matches and a lit roll of newspaper adequately provided the light required.

Defence in depth

A very impressive list of Second World War civil defence features, ARP shelters and bunkers and surviving anti-invasion features – both surface and underground – form the subject of this chapter. Air-raid shelters are the principal surviving civil defence sites in the Dorking area, and following decades of putting the past behind us, such places are now considered time capsules worthy of study and protection. School shelters can be real treasure troves, and Dorking has had a few. Sam reminds us that Surrey County Council built particularly good shelters. For organisations particularly loath to throwing things away, air raid shelters have proved to be very convenient places to lose and forget obsolete items. A 1940s shelter can contain the detritus of the 1960s, which in itself can be a fascinating source of history.

Trade secrets

Having read this far into the book, you will by now be fully aware that Dorking has been built on top of a bed of sand which proves ideal for hand-cut cellars and basements. Having been a thriving market town, Dorking has had many traders over the centuries. Each one has left its mark both on and under the town. Beneath a bland modern mobile phone shop or shoe shop there may well be an almost forgotten vestige of the pub, the butcher or the hardware shop that once occupied the building. With no use for the damp and unlit chamber below the modern premises, what was left there remains there, quietly gathering dust, rust and mould.

High Street, low street

Continuing the theme of cellars, basements and caves under the centre of the town, Sam tells us that the High Street, particularly on the south side, is eminently suitable for digging out tunnels and chambers, so much so, that it deserves its own chapter. There are more caves, more tunnels, wells and stairways. It’s all getting a little too familiar until you realise that every site has a unique story to tell, and patient research and exploration adds yet more to the story of Dorking. It is unfortunate that late 20th century redevelopment saw the destruction of several of Dorking’s caves, but we must hope that what remains is protected better in the future.

Tales from the crypts

You might think that a chapter entirely devoted to underground features of churches in Dorking would be limited to the odd burial vault; however, just like all the pubs and shops of the town, the churches were equally keen to have something underneath them. The parish church of St. Martin’s is particularly interesting, having been rebuilt twice since the original medieval structure had been in use for several centuries. The current building dates from 1877, and was placed several feet higher than its predecessor which has sunk below the level of the burials ground around it, not through gravity, but due to the ever-rising level of the churchyard with multiple generations of interments. This gave the builders the opportunity to keep a vault beneath the new church building, and in this chapter we learn about what remains down there – the most surprising feature being a roman well, still open. A 20th century youth club has left its evidence down there, and the usual debris of discarded history litters the place. But it was not only the Anglicans who could boast of underground space. The Society of Friends also had a cave where they kept fruit, coal and wood. Their earlier premises elsewhere in the town also had a cellar, into which, it is said, an entire congregation of 60 had descended when the rotten floor collapsed. It is with such anecdotes that Sam has coloured this book, and which makes it a delight to read. Not to be left out, the Baptist and Congregational church also had caves for some purpose or another.

Here runneth under

This section is concerned mainly with water sources and courses. Wells and springs are mentioned, early water supply systems using boreholes and the natural streams, and then onto the River Mole, not named because of the burrowing mammals the river is supposed to emulate, but more likely after mills that used its potential for grinding grain, or maybe after Molesey, where it disgorges its contents into the Thames. The nature of the numerous swallow holes is described along with an attempt in 1956 by the then young Chelsea Speleological Society to enter cave passages below the level of the river by digging out a crater which had appeared in Mickleham, swallowing an entire tree. Nothing was discovered, perhaps just as well, given that those early cave explorers’ minimum recommendation for safety headgear was a beret stuffed with paper.

Beneath the law

What could possibly remain that has not already been covered by earlier chapters? Well, clearly its basements used by solicitors. Dorking has a healthy population of civil law firms, and occupying large 18th and 19th century houses, they have adapted the basements and cellars, once used for storing coal, into strong rooms for all their important documents and paraphernalia. Even this brief chapter contains amusing anecdotes connected with the sites described. You don’t often find wig boxes when exploring underground sites.

Fields of stone

Surrey contains a surprising number of old mine and subterranean quarries, but these are concentrated further east. No doubt some sand extraction took place in the immediate vicinity of Dorking, but this section covers underground features at nearby limeworks and a chalk mine. There are some remains of kilns at Brockham and Betchworth, but underground features are limited to a few arches and passageways under the old 19th century lime-kilns. These are described along with some history of the hearthstone mining which took place here. One further feature described is a chalk mine, which are very common elsewhere in Kent and south-east London, but that near Dorking is unique for Surrey. It is now a very important bat hibernaculum. The site has little archaeological interest due to extensive collapsing, and is best left alone to benefit the various species of bat that use it each year. Sadly, this mine has been the target of mindless vandalism and deliberate destruction of the bat installations by people styling themselves as urban explorers. The site is not urban, and the activity could hardly be termed exploration. Such places are difficult to protect, and ultimately we can only rely on goodwill and common sense to have such places survive into the future.

Taverns in the town

We end our tour of Dorking’s underground with a pub-crawl. Being both on a coaching route and a market town, Dorking has had a lot of inns and public houses. It doesn’t take much imagination to guess how these premises created the storage space they needed, as well as cavities for other long-ceased activities. The former Wheatsheaf was notorious for its cockpit where the now long-outlawed activity of cockfighting took place. We are taken down into the tunnels below the former inn to see where this cockpit may have been. We can learn about the now demolished Sun Inn which had a labyrinth of tunnels below that rivalled the Wheatsheaf in complexity. The list of pubs both extant and long-closed goes on. Many of them have or had cellars and caves dug out beneath and behind them, and one wonders how much of the town has survived from all the burrowing into the sub-strata.

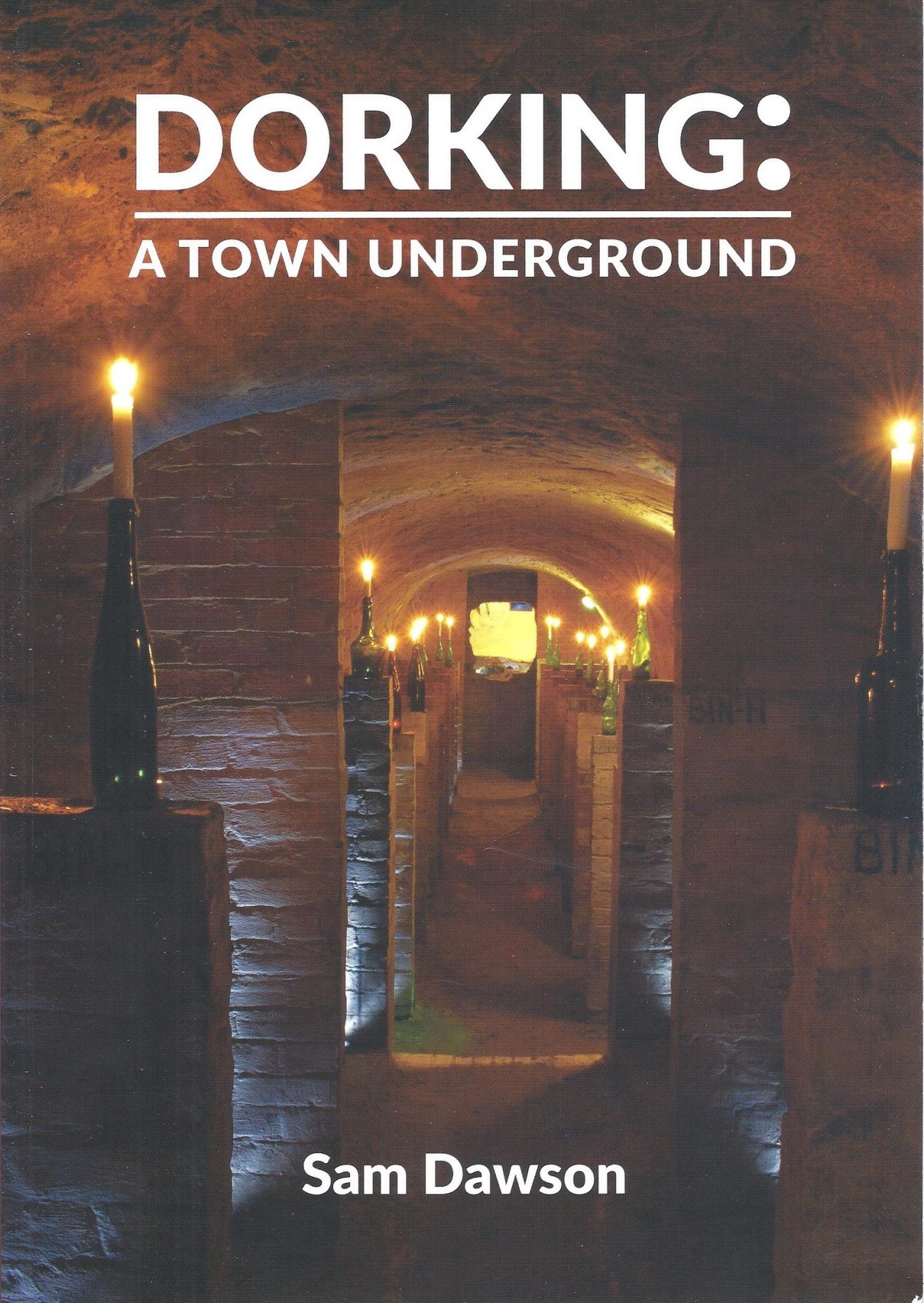

The whole book is lavishly illustrated with many excellent colour photographs and site plans which allow the reader to appreciate the fascination of the town’s caves all the more. All illustrations are by the author. Sam Dawson is a cave tour leader, journalist, and members of Subterranea Britannica and the Wealden Cave and Mine Society, as well as the Dorking Museum.

The book is published by the Cockerel Press, and available via the Dorking Museum website where you can visit the online shop.