It is impossible to either ignore or underrate this fine book, which is part of my triumvirate of classic cave writing dating from the 1950s, alongside Underground Adventure and Subterranean Climbers. Like many of its contemporary companions, the narrative relates how a group of adventure-seeking friends came together to explore caves and stumbled, almost by accident, (and certainly without permission!) into a major extension of the Cuves de Sassenage near Grenoble in 1947, raising questions as to the source of the Germe river therein, and hooked them into a career in cave exploration.

Having examined all they were able to at the rear of this well-known show cave, a study of geology led them to consider the Sornin Plateau as a likely sinkpoint for the river, and then the hunt was on. Nowadays so many UK cavers have been down the Gouffre Berger that it may be hard to comprehend all the circumstances of its discovery and difficulties surrounding its exploration. Here, a number of authors describe with admirable integrity how they recruited new members to their task and how they were affected on what developed into major 20-30 hour pushes – all conducted without modern exposure gear or sophisticated lighting.

The narrative initially details countless weekends spent delving into virtually every shaft on the Sornin lapiaz, with collective failure to discover the right hole until in 1953 Jo Berger happened upon the magic entrance. Over the following three years a series of weekend expeditions, ultimately extending into week-long camps underground, witnessed a punishing siege as cavers’ lamps gradually revealed more and more stupendous caverns, even more shafts, wet and dry, and other obstacles which required ingenuity and technical equipment to overcome.

The team, who eventually became the Speleo Group of the French Alpine Club, recount their discoveries in a most readable open style, admirably translated by RLG Irving. There is little need to read between the lines as, with frankness and artistry, various authors reveal their inner thoughts and truly reflect how young men sharing adventures bond together, their camaraderie and humour so familiar to modern club cavers. Considering the context, it is astonishing how conditions almost beyond tough spurred them on until in 1955 they were rewarded by achieving a depth of 1,130 metres (a record cruelly snatched from them by the Pierre St Martin at almost the same time).

An additional early chapter recounts their efforts in 1952 to shoot a colour film about cave exploration in order to explain to friends and the public just what drove them to spend so many hours exhausting themselves in dark, uncomfortable, hostile territory. The final production, entitled Rivière sans Etoiles (Starless River) is probably one of the first colour documentaries on caving and a very fine piece of work, retaining its freshness and excitement. Even today any opportunity to view this film is highly recommended.

One Thousand Metres Down should be required reading by anyone with more than a passing interest in caving. Despite being more than 60 years old, it effortlessly holds the title of best caving saga ever published and is unlikely to lose that crown any time soon.

Reviewed by Alan L Jeffreys

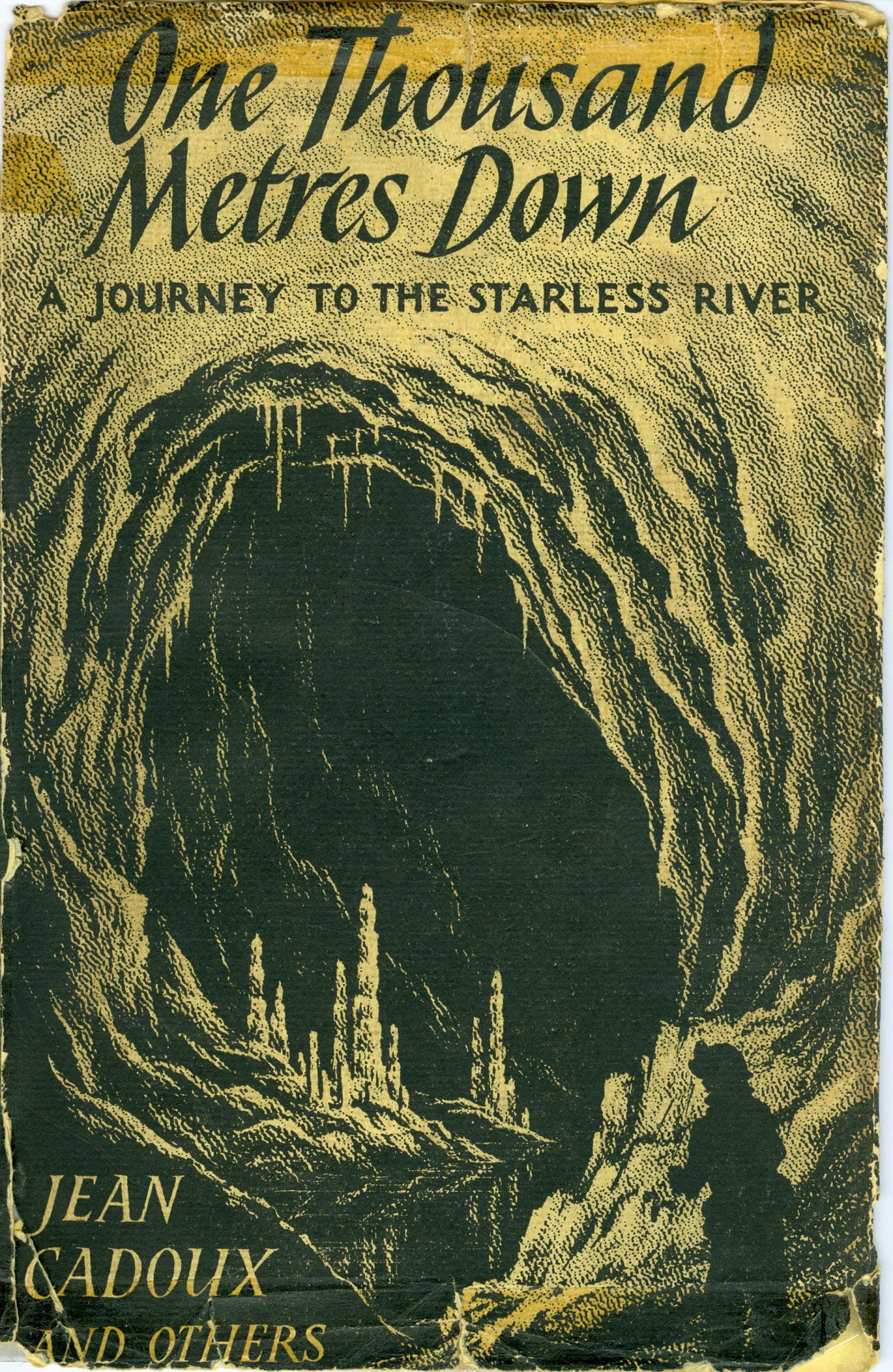

One Thousand Metres Down.

Jean Cadoux et al (translated by RLG Irving)

[French title ‘Operation -1000’, 1955]

Published 1957

George Allen & Unwin

179pp

23 plates

1 map

4 pages of surveys