On Saturday, 9th November 2019, the University of Bristol Speleological Society brought the public facing part of their centenary year to an end with a superb symposium, and attracted a good number of cavers to enjoy a day of fascinating talks on a wide range of cave science subjects.

It was early afternoon on a Friday, and I had succeeded in getting away from work as planned. This was the start of a weekend I had been looking forward to for some weeks. Getting away from anywhere close to London on a Friday afternoon is normally a bit fraught, so with an early getaway there was a good chance I would be able to join the start of the celebrations in Bristol, where the University of Bristol Speleological Society (UBSS) were celebrating 100 years of activity with a symposium and field trips, dubbed “Travels Beneath the Earth”.

All those attending the event had been invited to meet at the UBSS museum for some drinks and an informal “get to know you” session. Sadly, a few days earlier, someone from the university health and safety team had condemned the stairs in the building which meant that we were limited to the ground floor, but undeterred we chatted, ate celebratory cakes and drank while introducing ourselves and watching the younger UBSS members participate in some time-honoured cavers’ games.

The main event was scheduled for Saturday, and took place in the School of Geographical Science. Despite last-minute hiccups over the availability of a porter, everything was in place on time, with the event divided between two rooms, one with a reception desk, poster displays and refreshments, and the other a grand lecture theatre where all the presentations were to be made. Weeks of publicity bore fruit with 100 people attending the symposium.

It was a busy day of lectures, divided into four sessions: History and Archaeology, Exploration, Speleogenesis and Palaeoclimate, and UBSS Now and the Future. The speakers, mostly drawn from the membership of UBSS, covered a wide range of subjects and disciplines.

Andy Flack presented a summary of a series of 20 interviews conducted throughout the centenary year with significant members of the UBSS caving community. This included a number of memories not preserved previously in the written record. Andy demonstrated that there is more to cavers’ memories than a catalogue of activities, but it is equally fascinating to record how peoples’ feelings towards the cave environment can change, and often remain much the same over decades. Changing techniques and equipment can alter the way cavers interact with the subterranean environment by making cave exploration easier and a more comfortable activity. Most recently, the advent of the LED lamp has transformed how we penetrate the darkness and make the cave more visible.

Rhiannon Stevens of University College London spoke about new scientific methodologies used to investigate whether oscillating climates resulted in the ebb and flow of Neanderthals and different modern human groups in Britain, at a time when the region was a peninsula at the north-western limit of the European continent. This research has only been possible due to the survival of parts of the UBSS collections which curators had not disposed of, unlike other collections where such small bone fragments that prove so useful in this regard have been disposed of as being of little or no use. The analytical techniques deployed include stable isotopes, radiocarbon dating and ZooMS analysis (identifying species from surviving collagen and other proteins). The project emphasises the importance of “Old collections”.

The final speaker of the first session was Linda Wilson, UBSS museum curator, who argued the importance of recording graffiti in caves and mines, as a means to understand the history and use of subterranean space. For as long as humans have entered caves, we have felt the desire to record our presence, most frequently at the furthest limit of exploration. The dilemma of whether to remediate modern graffiti or not, can be a challenge, and we must we wary of projecting our current conservation ethics onto earlier generations. Recording inscriptions is an essential part of this process, and this can be achieved by simple record sheets and photographs, or by more sophisticated means using photogrammetry to create 3-D models of inscription features.

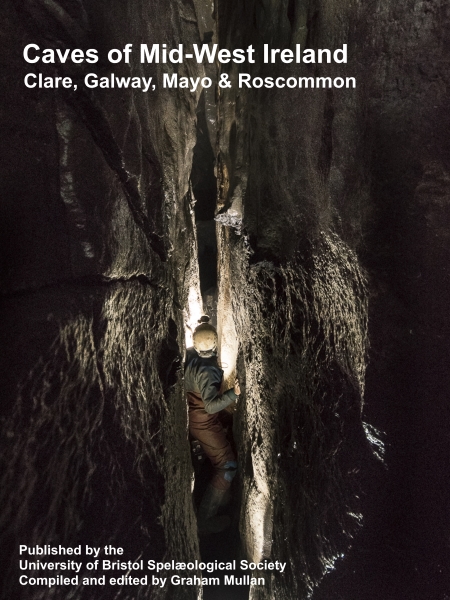

After a short break, the Exploration session started with Ashley Gregg focussing on recent visits by UBSS student cavers to County Clare, Ireland, and surrounding areas, to undertake survey update work in a number of the classic caves of the region. Ashley first provided a historical background to the society’s involvement in the study of the caves of the region, and briefly explained the cave surveying techniques used and how they have changed. Ashley has visited Ireland in four successive years from 2015 to 2018, each time to conduct surveying work, principally in the Coolagh River Cave, and the Cullaun Caves, but also at other sites, according to how much the weather permitted access to the exceptionally flood-prone systems. The work has greatly assisted in the publication of the latest guide book to the caves of the area, “The Caves of Mid-West Ireland”. The UK launch of this new book took place later in the day’s proceedings.

Elaine Oliver, UBSS President, followed with her impressions of a very different expedition involving UBSS student cavers, to The Totes Gebirge in Austria. Elaine informed us that UBSS students have joined expeditions to this area from 1981 until the present day. The extreme vertical and open nature of the caves is in stark contrast to caving in Somerset’s more horizontal and constricted systems. These Austrian expeditions have provided many UBSS student cavers with their first real taste of Alpine adventure. The Totes Gebirge contains Austria’s second longest cave system.

Dick Willis was the last speaker of the morning session. Dick is a UBSS veteran, and his story covers his early caving days from 1972, through to multiple expeditions to Sarawak to explore the caves of Mulu. Dick took us through the successive discoveries at Mulu, reminded us of some of the classic photographs taken in those early days in Mulu, and brought home to us what a momentous discovery it was at the time.

Lunch followed, with an opportunity to chat, and to look at the growing number of posters on display. The two remaining sessions of the day proved to be as interesting as those in the morning. Now the subject matter became much more topical, as Tim Atkinson of University College London discussed the application of speleothem dating to palaeoclimate studies, and the implications for climate change research. Early research in defining cave development is exemplified by the excellent work done by Derek Ford in G.B. Cavern published in 1964. The speaker described how, with the advent of new techniques to date speleothems using U-series dating, it revised the dates originally suggested from the Last Interglacial back as far as 400,000 years. With these new dating methods available, it became possible to determine cave development dates at least ten times older than previously. With this huge increase in range for dating, covering several climate change events, it is now possible to understand the complex mechanism of climate change, and Tim demonstrated how recent examples from Gibraltar have provided a detailed archive of temperature and the isotopic composition of rainfall during the Last Glacial.

David Drew then took us back to Ireland, to describe the karst and caves of lowland western Ireland, where, at first glance, there does not appear to be a huge amount of cave-related features in the landscape. David demonstrated how with the development man-made alterations to the drainage of the region since the nineteenth century such as artificial rivers, many karst features are no longer obvious. Turloughs, swallow holes and springs that were once very prevalent, now only manifest themselves during extreme weather events, with towns unexpectedly becoming inundated, hitherto unknown caves coming to light, and copious springs coming to life. There is still a lot to be learnt of this large area of Ireland.

Andy Farrant, of the British Geological Survey, presented the meeting with a summary of the various ways to read the history of a cave, by observing signs of former water flow and sediment deposition. Andy demonstrated how major changes in landform and climate can radically change the development of a cave, and that the evidence of this can often be found in the caves, but is easily overlooked, or misinterpreted.

The final presentation of the session before a tea break was to have been made by Pete Smart, but as he was unable to attend, Graham Mullan stepped in on his behalf. The talk covered the re-evaluation of excavated material and excavation reports from Pickens Hole, western Mendip Hills, where UBSS excavations took place from 1961 to 1967. Pickens Hole is a Last Interglacial to Holocene collapsed cave on a spur leading to Crook’s Peak, and was found to contain the remains of a significant number of largely undisturbed prehistoric animals.

Graham guided us through the complexities of the site, and the challenges of interpreting the finds which have been preserved in the UBSS collections. The National Trust, on advice from English Heritage, has cleared the area close to Picken’s Hole, but this has made public access easier and a new challenge is how to protect the near environs of the cave from curious visitors. Conservation of what remains of the deposits at the site is now a critical matter.

During the tea break, the meeting was joined by Councillor Jos Clark, The Lord Mayor of Bristol, and Nigel Taylor, the chair of Somerset County Council, both cavers. Jos was invited to join the judging team for the best student poster on display.

The symposium continued into the final session, and welcomed UBSS member Professor Rick Schulting from the University of Oxford, who gave the keynote lecture of the day, entitled “The darker angels of our nature: a butchered prehistoric human bone assemblage from Charterhouse Warren, Somerset”. Rick related the story of the butchered Bronze Age remains of over 40 men, women and children recovered from the cave at Charterhouse Warren in the 1970s and 1980s.

Rick described how the site of Charterhouse Warren reveals the darker side of our nature. Excavated in the 1970s, and dating to the Early Bronze Age, ca. 2200 BC, the scattered remains of at least 40 men, women and children were found in a 20m-deep pit. This largely unknown assemblage is striking for the sheer number of cutmarks indicating dismemberment, alongside perimortem fracturing of long bones and injuries to skulls. While evidence for violence is not unknown in British prehistory, nothing on this scale has been found, and the site joins a small number of Continental Neolithic and Bronze Age sites showing extreme violence and postmortem processing of human remains. Rick provided an overview of the new research being undertaken on the assemblage, documenting and characterising the extent of the injuries, investigating who these victims were, and understanding the site’s place in the wider context of the European Early Bronze Age.

UBSS President Elaine Oliver concluded the day’s presentations by summarising the many changes that the society has undergone, including the recent high profile involvement of the society in the evolution and function of the Council of Higher Education Caving Clubs (CHECC). But Elaine, as the society’s first female president was keen to emphasise the welcome high profile of female student cavers within UBSS and the long overdue recognition of their role within student caving.

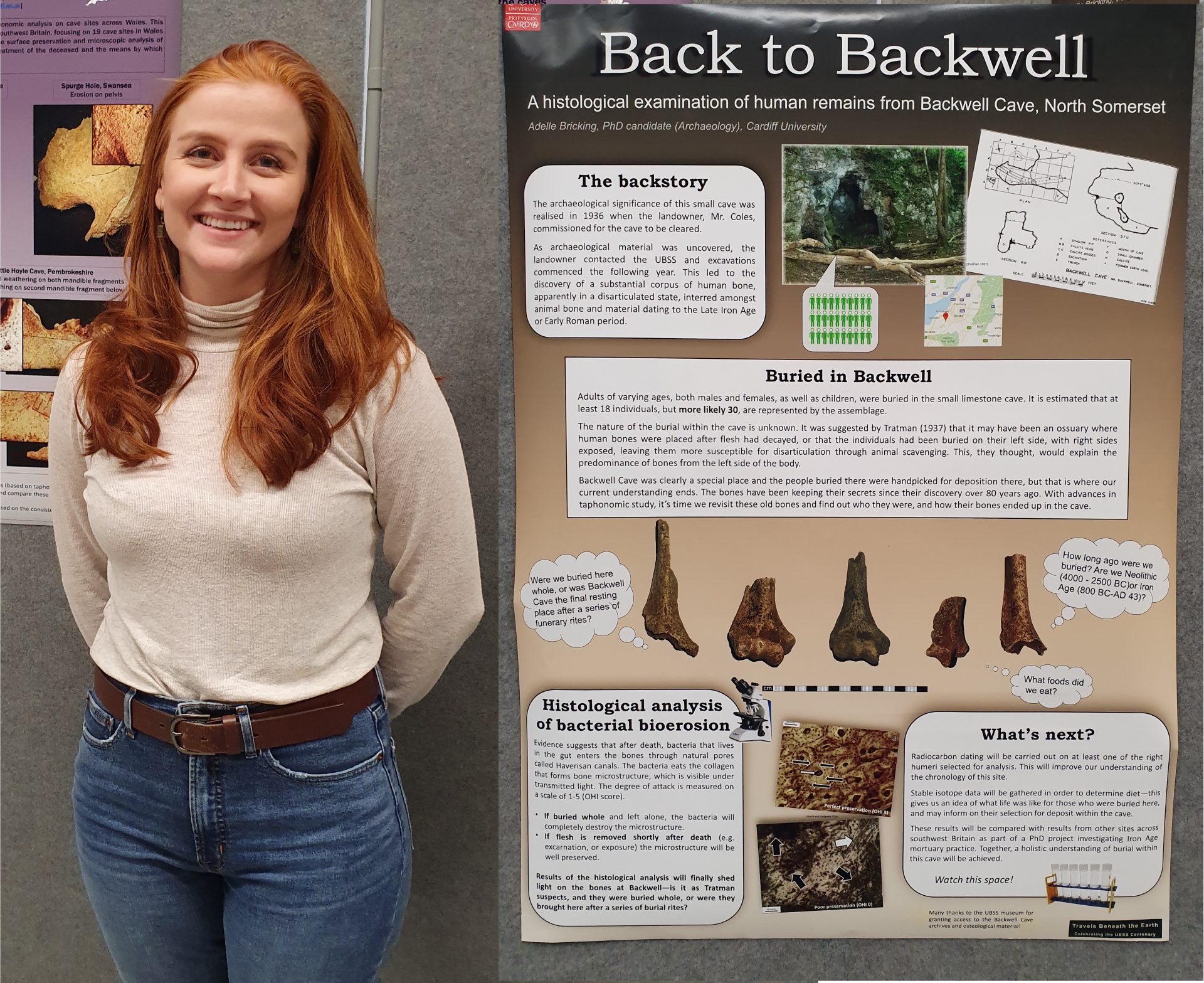

There was then a further opportunity to look at the poster presentations, and to promote the new book “The Caves of Mid-West Ireland”, compiled and edited by Graham Mullan. Published by UBSS in 2019, this book is available from the Society’s publications sales page. Further details of the book can be found here. The award of £50 to the creator of the best student poster went to Adele Bricking of Cardiff University, for her presentation of “Back to Backwell – a histological examination of human remains from Backwell Cave, North Somerset”.

Delegates had been invited to meet for drinks and a buffet in Brown’s, the busy restaurant close by, and a number of us enjoyed an informal evening of chat and relaxation. The day had been an all-round success, and a credit to those who planned it.

The remainder of the weekend consisted of field-trips on Sunday, and I attended Aveline’s Hole, where Linda Wilson and Graham Mullan met about ten delegates to explain the story of the cave, its discovery, and subsequent excavations. In contrast to the cave’s physical short length, it has a long and fascinating history. Early accounts of its discovery and a number of visits to the cave are recorded in contemporary newspapers, but unravelling an accurate chronology and the stories of those who made the early studies of the cave is a huge challenge. More recent excavations, and discoveries of inscriptions believed to be Mesolithic in date are better documented, and being the first cave to be properly studied by the UBSS, the cave was quite rightly at the forefront of the field trips arranged for the day. There were also trips to G.B. Cavern – another cave that has received much attention from the society, to Shute Shelve Cavern, and to Grebe Swallet.

It is a huge credit to those who arranged the events of the weekend, that it ran so well, provided a platform for some fascinating research and exploration work, and attracted a good number of both UBSS and non-UBSS delegates to benefit from all the efforts of the organisers.

Correspondent: Peter Burgess