In the second part of Darkness Below’s interview with BCRC chair Peter Dennis, he tells Linda Wilson and Sharon Wheeler how disaster struck during the preparations for the final rescue dives.

Disaster struck, though, on Friday July 6 as preparations were being made for the rescue dives. Former Thai navy SEAL Saman Kunan lost consciousness during his return to the surface and was pronounced dead at the dive base.

“We were shocked and saddened by the news of Saman’s death,” said Peter. “It marked a change in Thai attitudes that the navy divers couldn’t conduct the rescue unassisted. It was a tragic way to bring about a reality check after the euphoria of finding the boys. The navy divers were brave going into an environment that they had no experience of. Rick had aired concerns about their safety. We had great admiration for them, but they were diving in open-water kit. They weren’t used to diving in zero visibility with the use of dive lines and more complicated set-ups. They had back-mounted air cylinders, with no redundancy in their systems. In these respects, the risks they were taking were higher than the ones our divers faced, and ultimately it was tragedy for one of them. We’d learned such harsh lessons from losing colleagues earlier on in British cave diving history.”

Saman was retired, but very much respected by the navy divers and when he died, there was an understandable lowering of their mood, said Peter. This news was of grave concern to the team at home, emphasising the personal risks each diver took every time they entered the cave.

Despite tremendous efforts, the Thai divers had been unable to carry communications lines to the boys or indeed bring in the planned four months’ supply of food. In the end, the only food the boys had was what the medical team and John and Rick had taken in, plus two large deliveries of food carried in by Jason and Chris the day after they arrived on site, and a small amount taken in by the Australian team when they did their medical assessments the day before the rescues began. This should have lasted the boys about two weeks, but by the time the rescues began there was less than two days’ worth of food left.

“Then the assumption that the boys could remain underground until flood levels abated after the monsoon was challenged by news that air quality was deteriorating. The navy divers were unable to provide an air hose to improve the air quality in response. Our divers were certain that a dive rescue was the only option available to bring the boys out alive. There were quite a few things that changed the authorities’ minds and led to the decision to go for it,” said Peter.

“We were communicating with the Thai authorities via embassy and consular staff and with full support from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the message was – trust our people and their dive plan. The Thai rescue authorities were understandably nervous as they initially stated they would only act with a plan that carried no risk. Once they appreciated that the boys could not stay in the cave without even greater risk to their lives and after pressure from the prime minister and the king’s representative on site, they made the decision and approved the dive rescue plan devised by Rick, John, Jason Mallinson and Chris Jewell. It was made clear numerous times before July 8 that the boys had to be brought out – and there was only one way that could be achieved.”

The first dive through up to five flooded sections of cave alone was 350m long and required the assistance of further divers known to Rick, John, Jason and Chris. The role of the BCRC support team, coordinated by Emma Porter, was to find which divers were available and to arrange their transport to Heathrow to join flights to Bangkok. Two of them were overseas in Denmark and Italy at the time the incident started. Members of South East Cave Rescue Team and North Wales Cave Rescue Organisation volunteered to fetch Josh Bratchley, drive him home to Wales to pack essential kit and then quickly drive him down to Heathrow. Gavin Newman of the Cave Diving Group dropped what he was doing to shuttle divers based in the West Country to Heathrow. Thai Airways flew divers out in ones and twos using what were usually seats reserved for embassy staff. On arrival in Bangkok, each diver was transported rapidly to Chiang Rai on Thai military flights. For each diver in turn, a written justification of their role, flight arrangements, insurance and visas all had to be arranged through the tireless efforts of BCRC vice chairman Bill Whitehouse, in liaison with the FCO and British diplomatic staff in Thailand.

“As a consequence of all these efforts, the additional divers were on site when it mattered to make a difference,” said Peter. “Then later they had sufficient numbers to bring the boys out through the flooded sections. Some required dives of up to 350m, so they needed reliable, experienced divers to help them.”

The choice of additional divers was down to Rick, John, Jason and Chris and it had to be people they knew and trusted, said Peter. “A lot of other divers were turning up on site from many nations, but who weren’t known to the British divers. We were advising the Thai authorities that we didn’t know these divers, since some individuals had stated that they were part of the BCRC team in order to access the rescue camp. These may have included some very experienced and competent cave divers, but if it had been open there was the risk of things going wrong, so it was very much the call of the dive team out there who to bring in. Rick and John, together with Jason and Chris, and on the last day Jim, dived the boys out each day with support from the others stationed between flooded sections. Josh and Connor Roe were often the last to know how successful the dive rescue operation had been each day. The uncertainty made it very stressful for them because it was not until they emerged at the end of each day’s dive that they received that key information. Thankfully, each day they received good news that each of the boys was out safely.”

There was much speculation about the order in which the boys would leave the cave – would it be weakest or strongest, or biggest or smallest first? But it turned out that this was settled in the most rational way there was amongst close-knit friends…

“What transpired was that the boys had sorted it themselves. The first ones out would be the ones who lived furthest away because they had further to go before they would get a cooked meal from their mums! They didn’t realise at the time they would first be shipped off to a hospital quarantine ward for several days. It showed maturity and a generosity of spirit and provided an insight into how they worked as a team. When I heard of this, I smiled at the heart-warming basis of the decision!” said Peter.

Also the subject of much discussion in the media was whether the boys were conscious when they were brought out – something the Thai authorities were very nervous about divulging, not least out of respect for the feelings of family and friends of the stranded boys. Australian diver Dr Richard Harris – known as Dr Harry – was key to the dive rescue plan. He had dived to the boys with Rick, John, Jason and Chris each day of the rescue to provide medical supervision, along with a Thai doctor and nurse who had stayed in the cave with the boys since shortly after they were found.

“Dr Harry had to do a medical with each of the boys to ensure they were fit and well enough to do the dive. All were considered fit and healthy enough to undergo the traumatic experience of being dived out. It was a very sensitive area – the Thais didn’t want the world to know the boys were being sedated, not least out of respect for the feelings of family members anxiously waiting on site. But it was the only feasible way they could be removed from the ledge through treacherous sumps. The last thing you wanted was a sense of panic. If they’d panicked it would have compromised their lives and that of the rescuers,” said Peter.

Positive pressure face masks and valve adaptors had been flown in from the UK in preparation for the dive rescue operation. A scramble to acquire child harnesses proved not to be necessary because the buoyancy devices that were used provided a natural handle enabling the boys to be drawn through the water facedown. There was coordination between the Thai civilian police, the Thai navy and the US special forces who carried out the rope rigging to handle the stretcher each boy was placed in once they reached the sections of the cave accessible on foot. The stretchers could then be suspended by pulleys from tensioned ropes when the boys weren’t being carried by hand.

“Some local lads helped the cave rescue divers practice procedures in a swimming pool to check the suitability of kit so that they could see that the face masks and adapted wetsuits worked fine. It was great for those boys to have the opportunity to contribute something positive to help their friends,” said Peter.

One of the biggest challenges on the outside once the rescue was under way was managing wider expectations. And there was more to the operation than just rescuing the 12 boys and their football coach.

The BCRC received a reliable flow of information on the progress of the rescue, thanks to the presence of Mike Clayton and BCRC colleagues Gary Mitchell and Martin Ellis in the Joint Command Centre, who were logging divers in and out, helping with management and ensuring equipment and comms were ready and available to the divers, as well as doing liaison work with the Thai rescue.

“As soon as each diver and boy reached Chamber Three, we received an update – which number boy it was, and a status report on his condition, thankfully that each was alive. That was a very tense and anxious time, with concern for both cave rescue divers and the boys on each dive. We’d done all we could to get divers and equipment there. Our task was then to manage the eventualities. There was also the huge media excitement to manage,” said Peter.

And this included careful crafting of media briefings, where one of the main worries for Peter and the team was what they would say if any of the boys died. There was also a race against time with the deteriorating weather.

“When each boy came out alive it was wonderful. The last day was even more stressful, as the remaining four boys and their larger coach had to be dived out, which was more challenging with the extra person in the dive rescue planned for that day. It was also getting more and more likely that the monsoon rains would arrive, as there had already been periodic overnight thunderstorms. The water level stayed low, but rain was coming over the hill, so there was a push against the clock. Added to the tension of the last dive rescue day, the Thai doctor and nurse had to be assisted in their dive out, along with two other Thai navy divers who had been in the chamber with the boys for several days. So it wasn’t just getting the boys and their coach out – four remaining Thais had to be assisted out of the cave as well,” said Peter.

Just when it seemed that the rescue had been a success, there was last-minute drama for those still underground.

“Those navy divers were under orders not to come out immediately after the boys emerged. They were told to hang back in Chamber Three to avoid the media frenzy,” said Peter. “But suddenly one of the industrial mining pumps failed and there was a dramatic rise in water levels in 20 minutes. The instruction changed for them and remaining rescue personnel to get out as quickly as possible. So there was a dramatic and worrying period for an hour, an hour and a half, which was 4pm our time, while we monitored progress. Our hearts were in our mouths. The press were celebrating, but there remained others to get clear, including several BCRC cave divers, before it could be regarded as a success. When Josh and Connor and then the Thai divers were announced out, we could feel a huge sense of relief and gratitude for the divers’ skill and professionalism.”

Even with the boys rescued and in hospital, the media attention on the divers was still intense. Peter said there was a great deal of understanding that they had been doing a dangerous task, and that most media representatives had practised patience and understanding about the fact the BCRC is a voluntary charitable association – although Peter was asked on one occasion if they had an overseas office with staff available in the same time zone as the broadcaster!

“We had to explain that we’re just a small outfit, that ordinarily it is our teams that do operational rescues and that we represent them at national level. Only occasionally to assist rescue operations in other countries do we become the rescue team, such as with the rescues in Norway, Ireland, Mexico and France,” said Peter.

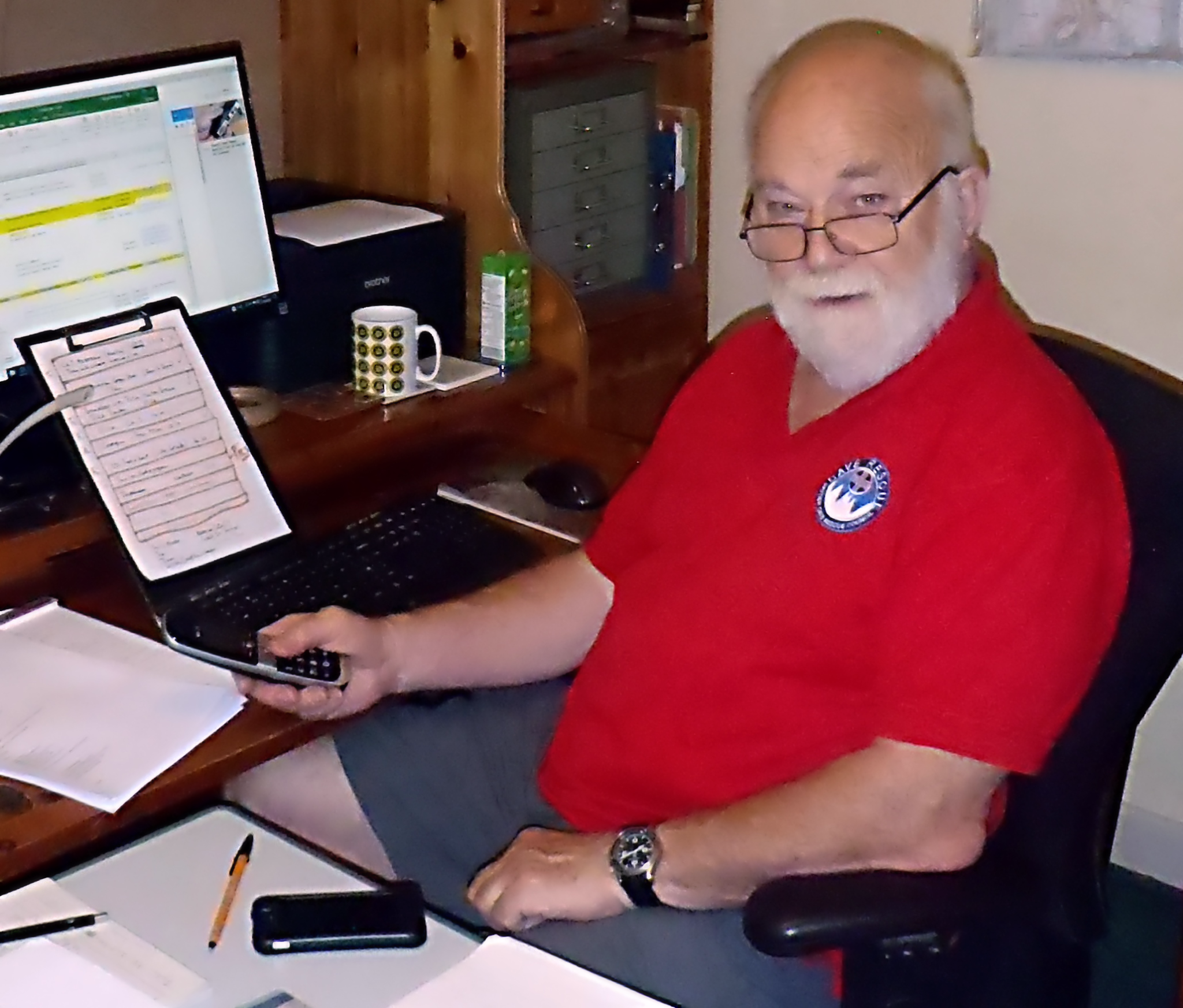

Even though volunteers have ostensibly gone back to their normal lives, there are still lessons to be learned from the rescue, added Peter, who is now settling down to write thank you letters to everyone who helped the effort, including understanding employers – among them his own vice-chancellor at Aberystwyth University where Peter is a Reader in Ecology.

“We had a debrief on what went well and what we might change. If we’re called on again, it would most likely be a completely different situation. It would almost certainly not be in the same country and the government and FCO contacts we’ve made will have changed or not be applicable at the time of the next request for assistance. There are some generic lessons to learn but the whole context would be different next time. With social media and intense media interest, we do recognise that we might be the first port of call next time there is a cave rescue incident in a country without a heritage of sports caving. We may now be perceived as the go-to group. Hopefully, though, it will be ten or 20 years before another incident, but it might not be. I’m so proud of everyone involved, including all the partner organisations in the caving community in the UK and across Europe who pulled together in support.

“Many individuals gave up evenings or days and demonstrated the excellent community among cavers, and all had a contribution to play in bringing the boys out. The boys have their lives ahead of them and I did wonder if they’d have survived if they’d waited longer.”

And Peter reflected on the fact that suddenly a load of unassuming cavers had become heroes across the world – something that also appeared to leave the media bemused!

“The media couldn’t quite understand the significance of the scruffy people wandering around the rescue camp in wellies and with their cave furry suits tied around their waists! They assumed that the navy guys, smartly turned-out and adorned with high-tech kit, were the heroes. They definitely called it wrong!”

Photographs courtesy of Peter Dennis