Reports on huge closed depressions in China, maze caves and bones from a site in the north of England are among the features in the latest edition of Cave and Karst Science.

There are six main articles in the volume 46 number 2, as well as some shorter pieces in the Forum section. The first is on the term tiankeng, meaning giant doline, by John Gunn, Yuanhai Zhang, Zenglin Hong and Qianzhou Luo.

The term tiankeng is used to describe extremely large and deep closed depressions that fall within the spectrum of dolines (sinkholes) but are sufficiently distinctive landforms to warrant their own name. It was introduced into the international lexicon of karst terminology in 2005 following a tiankeng investigation project in the South China Karst where the majority of the tiankengs known at that time were located. In this area the majority of these are largely independent of surface drainage and were formed from below by collapse. As a result, the 2005 definition included formation by collapse of a large cave chamber into a large underground river as a fundamental tiankeng property. A smaller number of erosional tiankengs that had developed at the site of a sinking allogenic stream were also recognised and regarded as end members of a spectrum of conditions, where collapse and dissolution vary in their relative importance.

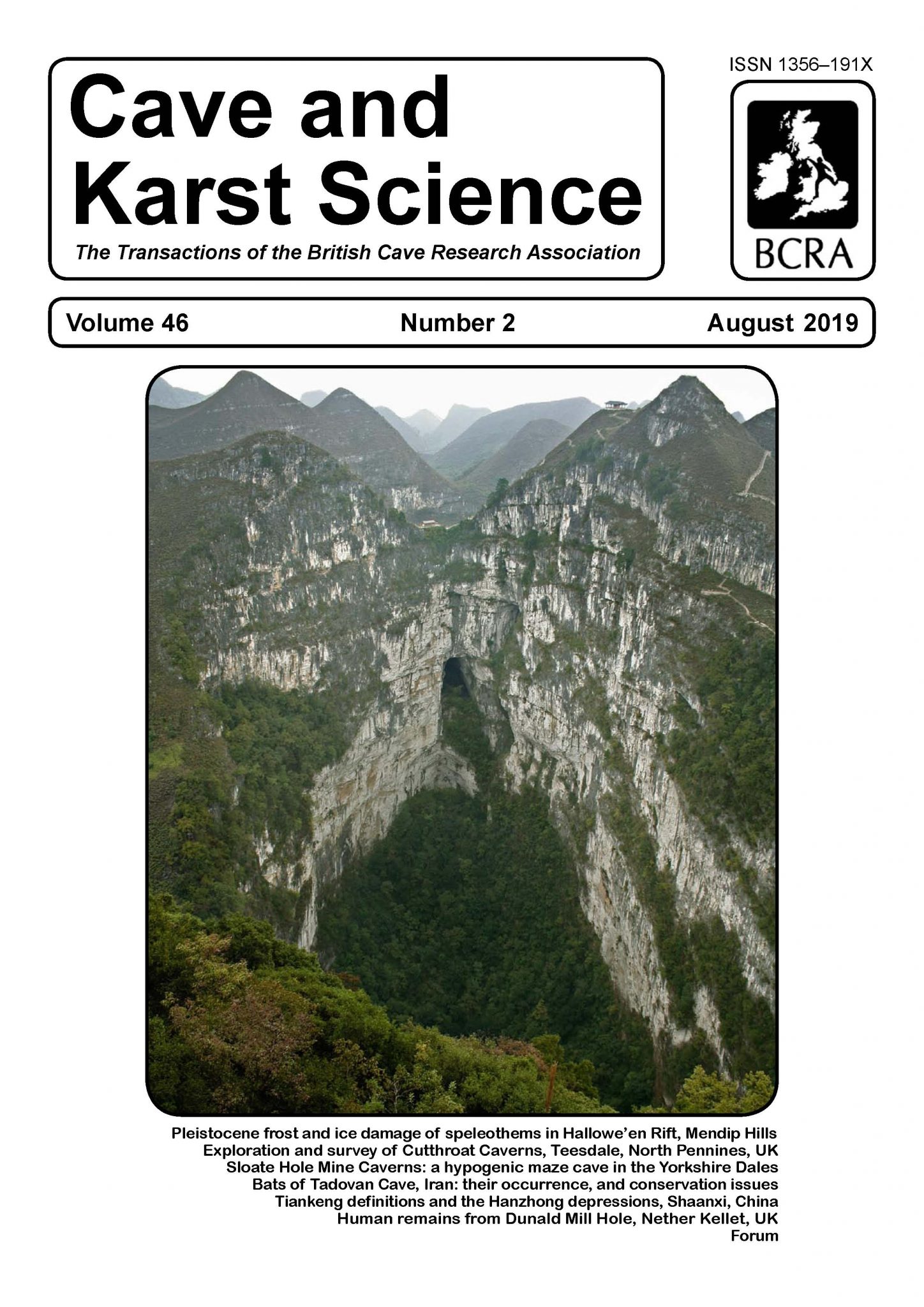

In 2016, 54 large, deep, enclosed depressions were identified in four karst areas south of Hanzhong City in Shaanxi Province, China and given the collective name of the Hanzhong Tiankeng Group. Four of these depressions were examined in March 2018 and the paper discusses their origins and how they fit into existing tiankeng definitions. There are no known underground rivers in the vicinity of two depressions and in the other two there is some doubt over the role of underground rivers in their formation. So although the Hanzhong depressions are magnificent landforms that meet the morphometric criteria for tiankeng they fall outside the present definition if it is interpreted strictly. To allow their inclusion, the authors suggest a modified definition: the term tiankeng is applied to enclosed depressions in karst that are over 100m wide and deep, have a small diameter over depth ratio (generally between 0.5 and 2.0), have a continuous perimeter with vertical or sub-vertical walls and were formed largely by collapse into an underground void.

This definition encompasses the classic tiankengs (where there was collapse into a void formed by dissolution and mechanical removal of limestone by an underground river); hypogenic tiankengs where the void was formed by hypogenic processes; and those erosional tiankengs where there was initially collapse into a void formed by limestone dissolution beneath a less soluble caprock.

Chris Curry and Tony Harrison look at the Sloate Hole Mine Caverns, a hypogenic maze cave in the Yorkshire Dales. Maze caves have been known for many years in the Yoredale Group limestones of the northern Pennines. At least nine network maze caves with plan lengths exceeding one kilometre and having more than ten loops have previously been reported, all but one accessed only via redundant mine levels.

Another maze cave meeting this length requirement has now been surveyed – Sloate Hole Mine Caverns in Arkengarthdale. Previously this was presumed to be a natural phreatic maze modified significantly by mining operations, but little was known of its geomorphology; a recent study of the site has shown that the mine is indeed primarily an enlargement of an extensive natural hypogenic maze cave with a surveyed length of 2.3km. Characterisations of this and of Cutthroat Caverns, another recently discovered large maze cave in Upper Teesdale and also described in this issue, enhance the hypothesis that hypogenic maze caves are widespread throughout the Northern Pennine region and that their genesis was assisted by acidity derived from nearby or intersecting mineral veins. But whereas the discoveries contribute to the geomorphological database covering this type of cave, much still remains to be determined about their exact mode of development.

Joshua Camerob, Diane Arthurs. Simon Cornhill, James Morris and Rick Peterson discuss the human remains from Dunald Mill Hole, Nether Kellet, Lancashire. A partial juvenile human cranium was discovered by Diane Arthurs during exploration of Pearl Passage in Dunald Mill Hole in late 2014. Radiocarbon dating established that the individual died between AD 5 and AD 225. Further excavation of the deposits within the terminal chamber of the passage recovered a small assemblage of other fragments and some faunal remains. All the human remains are likely to belong to the same individual, aged between three and six years at death, and to have been moved into the passage by flooding of the cave’s streamway. It is likely that the bones were eroded from further upstream rather than being deposited deliberately in the chamber where they were discovered.

Vince Simmonds looks at evidence for Pleistocene frost and ice damage of speleothems in Hallowe’en Rift, Mendip Hills, Somerset. Discoveries during 2018 revealed some interesting morphological features and an abundance of shattered speleothems. It had previously been suggested that this damage might have been caused by earth movements. However, after a close examination of the speleothems, it is apparent that the fracturing and related damage was caused by the actions of frost and/or ice during the Pleistocene. Uranium-series dating of speleothem samples has produced a range of dates relating to Marine Isotope Stages (MIS) 15–13, 7c, 5e and 3.

Over in southern Iran, Vahid Akmali Daeeid Shahabi and Mja Zagmaister have been studying the bats of Tadovan Cave in southern Iran, looking at their occurrence in the cave, and conservation issues. Caves present a crucial habitat for most bat species in Iran, but data on cave-dwelling bats are relatively scarce. Tadovan Cave in Fars Province is the richest cave in terms of bat species observed, with ten species recorded to date.

Data from published sources are listed alongside data from the present study, which includes three expeditions to the cave in March 2008, December 2013 and October 2015. An overview is presented of the cave chambers used by ten bat species from four different families: Rhinolophus hipposideros, R. blasii, R. euryale, R. mehelyi and R. ferrumequinum (Rhinolophidae); Rhinopoma microphyllum and R. muscatellum (Rhinopomatidae); Myotis blythii and M. capaccinii (Vespertilionidae) and Miniopterus pallidus (Miniopteridae). Microclimatic data of the cave chambers is provided, as well as body measurements of individual bats from the cave. A general decline in numbers of bat individuals is noted for all species, compared to visual counts reported from 1980 and 2012. Conservation issues are discussed, and urgent needs are raised both for systematic studies and for development of a detailed conservation plan for this cave.

Lastly, Chris Scaife and Ben Coult have been working on the exploration and survey of Cutthroat Caverns, Teesdale, North Pennines. A newly discovered maze cave with a total length exceeding 2.4km has been surveyed in Teesdale. Cutthroat Caverns is a highly unusual system. A natural entrance in a shakehole drops into typically epigenic vadose passages that lead into the apparently hypogenic phreatic maze. The cave takes its name from a nearby area of moorland known as Cutthroat Meas. Following a number of visits to explore, extend and survey the cave during 2018, the total plan length of the survey legs is 2424.65m and the vertical range is 16.65m. The survey is presented, alongside a description of the cave and its exploration. There are many mine workings nearby, and mineral veins appear to have contributed to the genesis of the maze cave. Joint and passage densities for Cutthroat Caverns are comparable to those at Hudgill Burn Mine Caverns and Knock Fell Caverns. Bat sightings in the cave are also discussed, including the presence of skeletal remains of Whiskered Bat, Myotis mystacinus.

Cave and Karst Science is published three times a year and is free to paid-up members of the British Cave Research Association. Members can also read it online here. Non-members may obtain copies for an annual subscription of £28 (plus postage for non-UK destinations). A discounted student subscription is available. The publication contains a wealth of information and represents excellent value for money for anyone with an interest in the science of caves. It is well-presented throughout, with a clear, attractive layout and numerous high-quality illustrations.