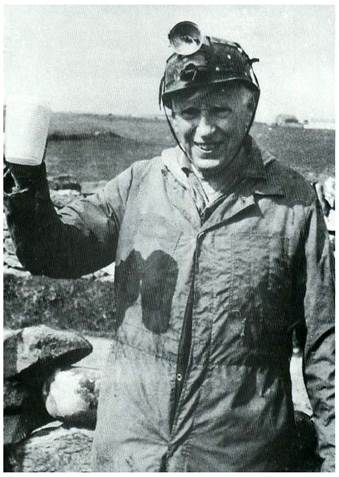

Camera expert Sid Perou looks back over a career of often dramatic and sometimes risky filming adventures, including the risk of foot fungus, and explosions under his stairs.

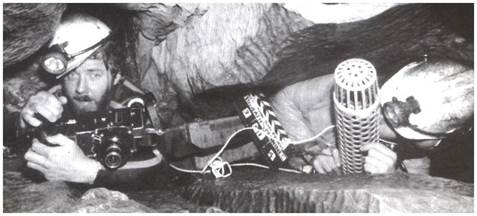

It is one of so many magical times that I will always remember … Lindsay Dodd and I were stood on the relatively flat top of a huge boulder. We were surrounded by a three-dimensional blackness that seemed so intense that, for the first time ever underground, I felt a kind of agoraphobia. Both of us felt a burning sensation on our feet, which we knew was the onset of Mulu foot, a fungal infection from the water that could rot the skin and leave your feet painfully raw. It was the first time we had entered the huge black void of Sarawak Chamber and we were there to film. I was thinking: “How the hell do I deal with this?”

Some days earlier, we had been filming on the trip when the chamber was discovered, but we were forced to turn back at a deep plunge pool and waterfall, having no way to get our film equipment across.

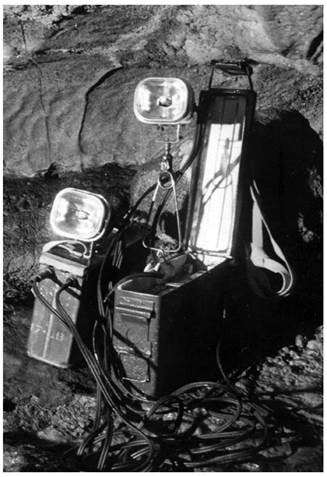

On the rock at our feet was an ex-army pack frame on which were strapped two car batteries, which we’d managed to buy at a store on our way up river in a longboat. I had been warned about the size of the passages in Mulu, and before I left England I had come up with the idea of mounting four 250 watt dichroic reflector bulbs, designed for film projectors, onto a 20cm length of aluminium angle, mounted on top of a short wooden handle. That gave me a kilowatt of lighting power which could be run by the two car batteries when wired in series. It needed big batteries as it was drawing more than 40 amps.

A second similar lighting pack was on Geoff Yeadon’s back in its way across the obstacle course, over car size boulders, to the far side of the chamber. That was a task in itself. We had two cheap radio handsets to communicate. When everyone was in position it became time to put the lights on.

I later described it like trying to light Wembley stadium with a couple of candles. We could see a lot more, but the film couldn’t. With the sensitivity of 16mm colour film available at that time, it was as good as I could achieve.

Lighting has always been the biggest problem, right from the earliest attempts to shoot film underground. The earliest attempts resorted to large magnesium flares. They gave enough light, but emitted huge clouds of white smoke. I once resorted to trying to use them, rather unsuccessfully, in the Main Chamber of Gaping Gill. The draught from the waterfall immediately caused a white smoke cloud to curl over and quickly obscure the shot. There could of course be no take two! What is more, we were forced to feel our way all the way back to Bar Pot in a thick magnesium pea soup fog.

The earliest filming in Britain was probably that done by EK Tratman in 1933. He used the big paraffin-burning Tilley lamps, used on building sites, to light his filming down Goatchurch Cavern in the Mendips. Even then the lighting was not enough and he was forced to run his camera at half speed to obtain a good enough exposure. Not only that but several of his team also suffered burns from the hot lamps.

In 1953, Eli Simpson attempted to make a 16mm caving film in Yorkshire. Faster film stocks were now available, but he came across the same lighting problems. He resorted to filming in Ingleborough Cave and elsewhere using a huge trailer-mounted petrol generator, needing thick cables and banks of 230 volt, 500 watt photoflood bulbs. This gave good results but needed a very accessible cave and the use of high voltages in wet cave passage was a considerable hazard in itself.

By the time I started filming in the mid 1960s, one thing had become available that made a huge difference: the quartz halogen bulb. It was compact, not nearly as fragile as photofloods and, as it ran on 12 volts, was much safer. The bulb was housed in a suitably robust reflector unit and powered by battery, so it was now possible to film in the small passages, wet crawls and remote underground locations that were and still are so much a part of caving in England.

Nevertheless, it still had many limitations. With the fastest films available at that time, with a maximum aperture of f1.6, the correct exposure was with the subject about only three metres from the camera. Now imagine a caver crawling straight toward you. When they are six metres away, they are two stops underexposed and by the time they get one and a half metres away. they are two stops over-exposed. There was no automatic exposure in those days.

So I had to learn lighting tricks. Other than in show caves, the light we see a cave by is from continually moving sources. I would try to replicate that using light movement, but, as I usually had different people holding the lights on every trip, it was never easy. Also, as the lights were constantly moving, any light meter reading was meaningless. I depended purely on what I saw through the viewfinder and of course at that time you would not know what it looked like until you got the processed film back days later.

Batteries were always a whole different problem. Some of the first ones I had used silver/zinc cells, which were built for me by the BBC. They were light, compact and excellent other than being expensive and with the large discharge currents I was using, they didn’t have a very long life. Also I only had two and I soon realised that I needed at least six.

Of course there were always professional lighting packs available but they were not within my budget and anyway, I suspected they would suffer and not last long under cave conditions. I found that two six volt motorcycle batteries fitted nicely into a medium-sized ammo box. They were a lot heavier, of course, but relatively cheap. They would give about half an hour light with a 100 watt bulb.

The problem was that at that time, they were inclined to leak acid. Wires and contacts inside the ammo box corroded mercilessly, giving me a lot of grief. When someone had carried a heavy battery to some distant location only for it not to work when they got there I got a lot of stick.

Then there was the charging. I needed to be able to put a number of cells on charge overnight. There was no fancy electronics available at my sort of prices, so I built my own. It used car bulbs in series with the batteries to control the charging current. That way you could see by the brightness the state of charge.

One lesson I learned early on. I used to charge in a little enclosed storage area under the stairs. One night I had forgotten to open the ammo box lid to allow the cells to vent during charging. The result was a compressed mixture of oxygen and hydrogen inside. When I came down next morning I decided to test the state of charge by plugging a light in. Somehow that caused a spark on a bad internal connection. There was a loud explosion right in front of me as the lid of the ammo box was torn off and knocked a chunk out of the ceiling and the ammo box sides bowed out dramatically. I was in shock but somehow nothing hit me.

There are far too many other such stories to relate here, but needless to say I look at the modern technology and just wish I was young enough to do it all again.

Cameras are now as sensitive as the human eye, plus LED lighting that in every way surpasses anything that I had, not just in portability, but also in reliability, duration and lightness.

HD video in a compact camera gives quality I could only dream of. And where one 100ft 16mm roll of film lasted two and a half minutes, a small memory card can hold an hour or more of quality video. What is more you can see exactly how your lighting is working as you shoot it.

And there are drones and GoPros, all at a fraction of the price my equipment was all those years ago. But then again has it all become too easy? Take a look back at how it used to be:

Of course caving video clips are common on Youtube these days. Most are a piece of admittedly nice footage with not much editing and far too often a single piece of often inappropriate music from end to end. There are still only a few properly filmed, well-edited and well-crafted documentary videos being made.

As far as television goes, the possibility of getting an independently made caving film on television these days is virtually nil. If they make something themselves, they must have their presenters in it. In fact, it is their fear that it might not work that so often prevents it from working. The presentations so often finish up feeling somewhat synthetic.

I remember talking to Gavin Newman about his filming in Peak Cavern and Titan Shaft. He related how the presenter’s piece to camera had virtually been pre-written and how the original explorers were not allowed down because they did not have the appropriate health and safety certificates.

Sorry, Health and Safety, when I was playing, we broke every rule in your book but got away with it because the people I worked with knew what they were doing. Perhaps then, on reflection, I was better off doing what I did when I did it.

Article and photographs courtesy of Sid Perou