Linda Wilson picked up some intriguing tips at the British Cave Research Association’s 29th cave science symposium as well as drinking plenty of tea …

If you wanted to find out how to annoy our cross-channel neighbours, which caves you might want to avoid if spiders aren’t your thing and why you might soon be sitting in the pub with data relayed to you, then the BCRA’s symposium was the place to be.

The School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol hosted the event on Saturday 13th October 2018, providing a spacious room for the poster presentation and for socialising over tea, coffee and biscuits. The lecture theatre was roomy with a good set-up for the talks and there was none of the flap over malfunctioning technology that characterises most conferences. David Richards was an excellent host and made sure that the important things were taken care of, such as plenty of boiling water for drink, as for me there’s nothing worse than a conference where I can’t drink copious amounts of tea. He even managed to induct me in the arcane workings of the large departmental vacuum flasks!

Doors opened for registration at 8.30am, and everyone took their seats at 9.15 for a welcome from BCRA chair John Gunn. The symposium ran with refreshing attention to time throughout the day, with the first presentation starting promptly at 9.30am with Rob Watson talking about Fifty Years of Sinkholes, Subsidence and Salt Erosion of an Evaporite Karst Landscape on the Eastern Shore of the Dead Sea in Response to Base Level Drop. The background to this is that the rapid regression of the Dead Sea since the 1960s has created a unique environment for “the study of the development of evaporite karst geomorphology due to the fall in base level of a hypersaline lake.”

Numerous sinkholes pose a major hazard to infrastructure and agriculture as they lie typically very close to the surface and are easily eroded by water, particularly after rain. Rob showed some impressive film of holes in the ground rapidly forming and collapsing that reminded me of an art installation I saw once in a museum! The study used very high-resolution aerial and satellite data to record the development of over 1000 sinkholes since the mid-1980s and the pattern of their migration.

This was followed by Andy Farrant who talked about The Chalk – The UK’s Most Important Karst Region of All and as Andy works for the British Geological Survey, it’s fair to say that he knows a thing or to about karst regions. Mentioning karst to cavers will usually end up with a list of classic caving areas, and even a few not-so-classic ones, although most people wouldn’t even think of the Chalk as being karst but, as Andy explained, it displays all of the classic land-forms associated with more classical karst areas, including sinking streams, sinkholes, large springs, rapid sink-spring transit times and cave systems. Andy focussed on the style and nature of karst in the Chalk, the type of conduits and cave development present “and their relationship to inception horizons and chalk lithostratigraphy.” Without wanting to appear sizeist, the caves were mostly pretty small, and you’d have to be fond of crawling to go very far!

Matt Rowberry gave some fascinating insights into Monitoring Subterranean Fault behaviour using a Contactless Positioning System. Matt studies mechanical discontinuities such as faults and joints to work out what constraints there are on their behaviour and what processes are responsible for their movement. He uses a contactless positioning system for monitoring fault behaviour and he brought one of the units – a small, oblong black box – along with him.

An 18-month field experiment investigating the influence oscillatory phenomena exert on fault behaviour has been conducted at Altaquelle Cave near the village of Brunn bei Pitten in Lower Austria. Two of the criteria for selection were electricity and wi-fi – things no self-respecting cave should be without. Faults both on the surface and in the cave were monitored using magnetoresistive sensing arrays and control units. Matt’s abstract commented that: “Recent advances in the contactless monitoring system have replaced the neodymium magnet with an electromagnet in order to achieve unprecedented instrumental sensitivity.” Despite a lot of unfamiliar terms, the talk was fascinating.

After the first break, Andrew Smith talked about The British Cave Monitoring Centre – Latest Developments and Opportunities. Work started in 2017 at Poole’s Cavern in Buxton to establish the first long-term cave monitoring centre in Britain. The idea behind this was to find and develop a secure cave site that could be available for use by anyone interested in cave science. The hope is that the site will facilitate more cave research projects in Britain and add to the understanding of cave and karst processes.

A variety of research projects are now underway and instrument provider Tiny Tag have equipped the cave with the latest radio loggers. In the ultimate armchair caving tradition, data is now fed back to the entrance so that research can be conducted without researchers even needing to go underground. With more resources, data could probably even be streamed to a local pub! The project is funded jointly by the BCRA and the Buxton Civic Association, who own the cave. The idea of a permanent home for research is to counter short-termism in cave research and to this end funding has been committed by both organisation up to 2023.

Anyone with arachnaphobia would have been well-advised to take an early lunch break, as Daniel Simonson started showing pictures of scary spiders in his discussion of Web Characteristic Comparisons between Meta menardi and their Non-Troglophile Relatives Metallina mengei and Tetragnatha montana. Meta menardi is the only Latin name for a spider I know, the result of frequently going underground with the late Charlie Self, usually in stone mines where he would take great delight in pointing out to his more squeamish companions vast numbers of ‘fat brown spiders’ that could easily have been the first cousin of Shelob. Daniel’s work on orb web spiders shows that the webs made by Meta menardi are quite different from those of their surface-dwelling relatives, as their webs usually lack frame sections. The talk included, amongst other things, the fascinating facts that Meta menardi catch and eat slugs and that the female of the species can live up to ten years.

The BCRA AGM was held at noon, and then a leisurely lunch break allowed plenty of time for chatting and looking at the excellent poster presentations. I was particularly fascinated by the one entitled A Possible Neanderthal Ritual Cave on the Gower Peninsula, South Wales from John Cooper, Gina Moseley and Vince Simmonds. This deals with HT Cave, a previously unrecorded cave, close to the southern cliffs of the Gower Peninsula.

Over thousands of years, the cave filled with rock, scree and sediment, but excavations in the upper chamber have revealed “objects deposited in niches in the cascading flowstone walls, step features on the walls and a possible image in an alcove. These all indicate human activity and provide possible evidence that, at some time in prehistory, ritual practices took place in the cave.” Nearby evidence indicates that this area was a Neanderthal hunting territory. The photograph shows deposited items that reminded me strongly of objects I’ve seen cached in other caves, notably the Palaeolithic sites of Les Trois Frères and Enlène in the French Pyrenees. The work in HT shows that the human impulse to place objects in wall niches stretches back even further than might previously have been believed.

Lee Knight and Lou Maurice presented a poster called The Aquatic Invertebrate Fauna of the Ogof Draenen Cave System in South Wales. From 2012-2015, an extensive investigation of the various aquatic habitats in the cave was undertaken, ranging from small pools to the extensive number of active stream-ways present. Numerous species were recorded including some found for the first time in a Welsh cave system. Eirini Konstantinidi presented a poster called Going Underground: Patterns in Human Taphonomy in Neolithic Caves and Burial Monuments in Wales and Southwest England. Her work employs targeted taphonomic analysis to create a profile of mortuary deposition within these regions.

Vince Simmonds had a poster with some initial observations on Evidence for Frost and Ice Damage of Speleothems in Hallowe’en Rift, Mendip, where recent discoveries in during 2018 have revealed some interesting morphological features and an abundance of shattered speleothems. Originally it was believed by some that this damage had been caused by earth movements, but after a close examination of the speleothems it‘s apparent that the actions of frost and/or ice during the Pleistocene have caused the fracturing and damage.

Jo White and Philip Hopley‘s poster was on Yorkshire Dales Cave Climate Monitoring, the work Birkbeck and University College London are currently undertaking into rapid climate events in the early Holocene using speleotherm samples from Yorkshire Dales caves and a variety of methods including temperature and drip rate loggers situated in the caves along with hand-held temperature, CO2 and relative humidity readings. The project began in August 2016, and the poster provides the findings two years in, along with future progressions and objectives for the project. All the posters were high quality, with information presented clearly and concisely, as well as in a very visually attractive way.

After lunch, Alistair Pike took the stage for the 40-minute keynote speech on Neanderthal Cave Art and the New Origins of Human Symbolic Behaviour describing cave painting as “one of the most intimate windows into the minds, beliefs and symbolic capacity of our ancestors…”. However, studies have been hampered due to the difficulty of dating them. Alastair explained that “radiocarbon based chronologies for cave paintings remain controversial since the application of radiocarbon is restricted to organic pigments and suffers from issues of contamination.” In addition, stylist methods often end up being wholly circular in their argument.

The approach of the team he works with has been to use Uranium-Thorium dating of carbonate deposits formed on top of paintings to constrain their age. Their recent work has shown paintings in three caves in Spain to be more than 64,000 years old, which predates the arrival of modern humans to Europe by at least 20,000 years, with the inevitable conclusion that the paintings must have been made by Neanderthals. This has profound implications for the understanding of Neanderthal symbolic behaviour, and the timing of the evolution of capacity for such behaviour. The research, particularly on negative hand stencils, amply demonstrates that a premeditated process was at work and as such equates to symbolic behaviour.

The work unleashed a storm in some sectors of the archaeological world and promptly resulted in outraged cries of (in French) “that wants stopping!”, as my dad was fond of saying. The team was equally promptly banned from doing any sampling work in France, which ignores the fact that the amount of stal needed for the technique to work has reduced dramatically from 100g to 10mg and is now at the minimally invasive 1mg!

The argument that broke out over the work reminded me forcibly of the stubborn refusal of the French to credit Marcelino Sanz de Sautulola with the discovery of Palaeolithic cave art in the cave of Altamira in Northern Spain in 1879. Emile Cartailac’s belated Mea Culpa d’un Sceptique in 1902 came too late for the unfortunate de Sautuola, who had died 14 years previously, still under the shadow of the accusation that the paintings were fake. With this in mind, it’s nice to know that Alistair and co are continuing a long tradition of pissing off the French when it comes to matters relating to cave art (even though I firmly believe that Glyn Daniels was talking out of his arse where Rouffignac is concerned, but that’s another story entirely).

Alistair was a hard act to follow, but Konstantinos Trimmis rose to the occasion with a talk on Recovering the Lost “Atlantis” Landscapes: Presenting a Non-Invasive Methodology for Archaeological Cave Field Survey in the Context of Santorini (Thera) Island, Greece. His aim was to address the lack of a clear methodological framework for undertaking an archaeological survey/evaluation and recording of artefacts and features in situ, where methods such as fieldwalking can’t be employed for problems such as low ceilings, narrow passage and other natural features as most archaeologists don’t have the advantage of also being cavers. He talked about the role of the ‘Discovery Unit’ as an interpretational aid, which looks at wider areas than the traditional more narrowly focussed archaeological unit.

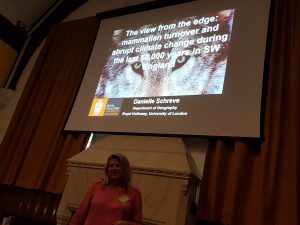

The archaeological session continued with a talk by Danielle Shreve on The View from the Edge: Mammalian Turnover and Abrupt Climate Change During the Last 60,000 Years in SW England. Danielle focussed on the work she’s carried out over a number of years in Gully Cave in Ebbor Gorge, Mendip where an extensive excavation has yielded some 1,700 large vertebrate remains, with 100,000 microfaunal remains.

The question Danielle has been seeking to answer is whether species move, adapt or die during periods of climate change. The session reinforced the view drilled into me over the years by Andy Currant that voles are important! And so are collared lemmings, as the study has revealed unexpected waves of population. The quality of the microfaunal remains from the site is excellent as the layers in which they are found were capped by a layer of flowstone that prevented later damage from badgers – the bane of many an excavator’s life.

In Caves of Wonder: A Preliminary Analysis of the Faunal Assemblages from the Covesea Caves, NE Scotland, Alex Fitzpatrick looked at a series of later prehistoric sites located on the Moray Firth. Human remains have been recovered from several of these caves: the Sculptor’s Cave, Covesea Cave 1 and Covesea Cave 2 and display unusual characteristics that may indicate complex ritual and funerary practices. Faunal assemblages from the site are the focus of Alex’s research and she is examining the role of animals at the site, as well as investigating the complex funerary treatments to which the human remains were subject.

The caves are hard to reach, and because of an accident on her first attempt to visit them, her research has been conducted at a distance, with no further site visits. The talk, although interesting, provided the only moment during the day that caused my museum curator’s soul to shrivel in horror when a question was asked at the end as to what arrangements were being made for the long-term curation of the remains once her research has ended, which she was unable to answer. In my view, unless it’s an urgent rescue dig, nothing should ever be dug up until the question of long-term curation has been answered, otherwise material is all too easily lost or, worse, simply disposed of once a study ends.

The final lecture of the day proved the value of depositing material after excavation in well-curated museum collections. Graham Mullan talked about Bone Hole, Cheddar Gorge: Archaeological and Paleontological Collections, where material was excavated first in 1838 and later in 1976. About 25 individuals were interred in the cave, reportedly including one possible crouched burial. Four radiocarbon dates have been obtained on human specimens. The earliest dated burial comes from the Early Bronze Age and the latest from the 8th century AD, with faunal remains from Neolithic and later times.

The only archaeological finds recovered were an early Beaker, a small sherd of Samian pottery and a burnished blackware pot probably dating to between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD. Graham told the story of how some of the human material in the Bristol City Museum was wrapped in old newspaper from 1916, which recorded events at the siege of Verdun and the battle of the Somme. The material might not have been looked at for many years, but it was still safely accounted for and available for study.

At the end of the symposium, about 20 people followed me up the hill for a visit to the University of Bristol Speleological Society museum and then some of us rounded off the day with an excellent meal at Zero Degrees, kindly organised by Gina Moseley. I wasn’t able to stay for the field trip to GB Cave on Mendip, led by Andy Farrant, and had to confine my underground experience to the Channel Tunnel instead. The whole day was well-organised, informative, entertaining and very sociable. The symposium was captured by the expert pen of artist Dominika Wrøblewska and I’m grateful to her for permission to reproduce her drawings. You can find more of her work here.

Correspondent: Linda Wilson