Creswell Crags is an Site of Special Scientific Interest on the border of Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. The beautiful limestone gorge cuts through an area of higher topographic relief that contains a series of horizontal caves that are perpendicular to the gorge itself. Several caves were first used by Neanderthals 50,000–60,000 years ago age followed by a short occupation around 32,000 years ago during the last ice age. After that, all the main caves were in use around 14,000 years ago.

The caves contain the northernmost European cave art of the Late Pleistocene; with some panels having been dated to the late Upper Palaeolithic by Uranium/Thorium disequilibrium dating of overlying flowstone to before 12,800 years ago. The seasonal Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic nomadic visitors were followed by people in the Neolithic, the Bronze Age, the Roman period and more modern activity.

Martin Hunt, a caver who knows the site well has sent us the results of some recent photographic work he’s carried out at the site.

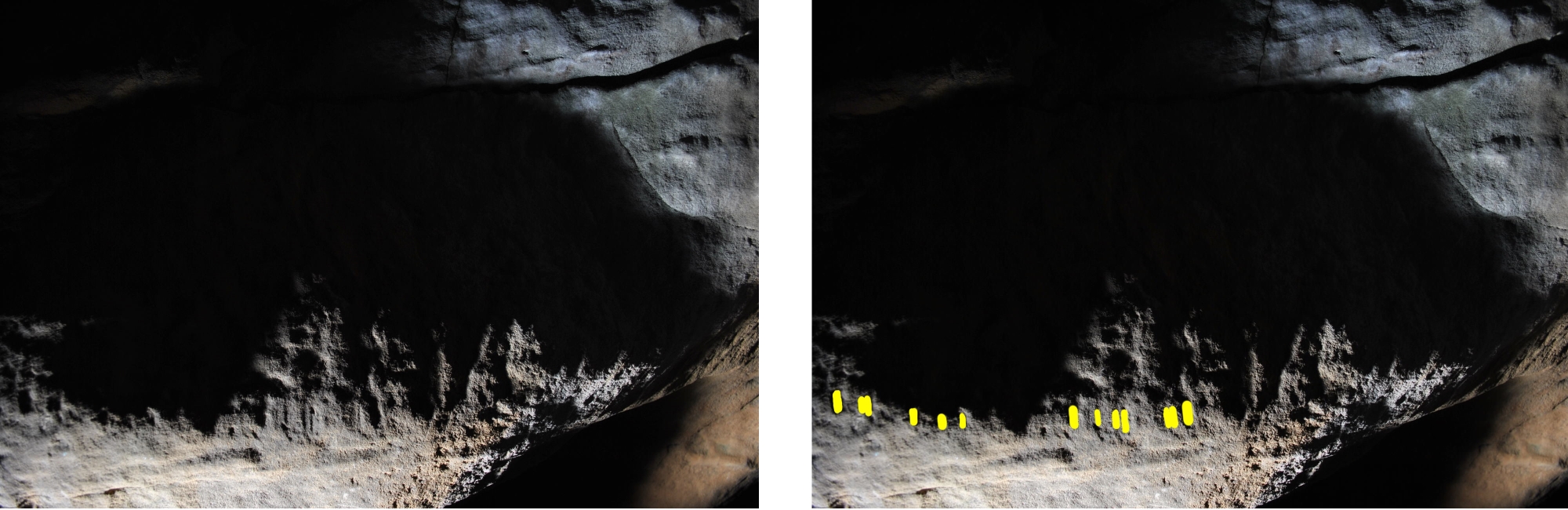

The images above are from Church Hole at Creswell Crags, where Martin was hoping to capture as good an image as possible of the well-known ‘bovid panel’. He told us that during this work, some additional marks just below the main panel ‘visually popped out’. These can be seen in two images here, with the marks shown in yellow on the right hand photo above. These are similar to ones described below the “deer” panel in the cave (see Bahn, P. & Pettitt, P. B. (2009). Britain’s Oldest Art: the Ice Age Cave Art of Creswell Crags. English Heritage.) but the marks Martin noticed do not appear to have been described anywhere.

In Martin’s opinion, the marks could represent grass as well as being tally marks, possibly used as a way of keeping track of how many animals had been hunted. Although it’s a reasonable assumption, there’s no firm proof that the marks were contemporaneous with the bovid engraving but an informed guess suggest some contextual relationship is likely. The engravings at Creswell that have been dated are contemporary with the evidence for occupation during the late glacial interstadial around 13,000–15,000 years ago.

Martin has made a film of the bovid panel using a technique called PTM (Polynomial Texture Mapping), originally developed at HP Labs by Tom Malzbender. The idea is to integrate a lot of static images (approximately 60 in this case) with raking light from different directions into one smooth movie file but with the added trick of changing the reflectance of the surface to something where the human eye can more easily identify dull and non-reflective features.

Correspondent: Martin Hunt.